Posted by Lauren Parsons

Whether it’s fighting for representation or fighting for a cause, art and activism share an intertwined history. The recent slurry of soup-based defacements of famous artworks staged by climate activists in high-profile galleries around the world, has set a rather unlikely stage for the two to meet.

Activists from Ultimate Generazione in Milan, Extinction Rebellion in Melbourne, Just Stop Oil in London and The Hague and Letzte Generation in Potsdam have all strewn a range of gloopy foodstuffs across (and in some cases even tried to attach themselves to) works from Goya, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Vermeer and more.

One of these incidents in particular, which took place on the 14th of October at around 11am in Room 43 of the National Gallery, saw two protesters in their early twenties proceed to throw a can of what many assume to be cream-of-tomato soup over Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers.

As they did this they chorused the phrase “What is worth more? Art or life?”

In this performance of shelf-stable tomato soup and confounding phrases – the activists created a theatre wherein art and life were not only mutually exclusive, but two forces in active opposition. Whilst Van-Gogh’s Sunflowers, a famous historic and culturally significant work of art, was refashioned into a subsidiary part to serve their larger, more physical and audible depiction of a present-day protest.

Just Stop Oil activists in action. (Source)

It is impossible at this point not to refer back to a similar incident, also taking place in London’s National Gallery, more than 100 years prior. On the 10th March 1914, Mary Richardson slashed into the canvas of Velázquez’s Toilet of Venus with a meat cleaver.

According to Richardson, her attack on ‘the most beautiful woman in mythology’ symbolised her protest for the release from custody of her suffragette comrade, Emily Pankhurst, who she referred to as ‘the most beautiful character in modern history.’

Both Mary Richardson and the Just Stop Oil activists wanted to shock, whether by soup or meat cleaver, however momentary or lasting, they publicly defaced a work of art that held cultural value – giving an aesthetic, visceral recognition of their rallying cause to a captive audience.

In the above scenarios the art is merely an intermediary between the activists and the establishment – but I would wager that there are better routes to this. Art and activism aren’t forces in opposition. They are actually comrades of sorts – both usually take form as experimental, sensory acts that seek to convey a meaning – normally captured within a public space. Protests can be peaceful, art can disrupt, and the roles can obviously be reversed.

As someone who has studied, and spends a lot of time admiring similar types of paintings to that which the activists have made headlines for splattering with liquidised foods, I find myself stuck between respecting the activist’s techniques of protest and wanting to suggest alternatives. I wholeheartedly agree, the status quo must be shaken to incite real change and in a world of such inequality, activism must take various forms.

However, art, for many, is about leaning into the rebellious and I can’t help but think that it is when art and activism work in-tandem that more substantial messages can be crafted – leading us towards more important, nuanced conversations about critical issues such as climate change.

Here are three artists who are doing just that:

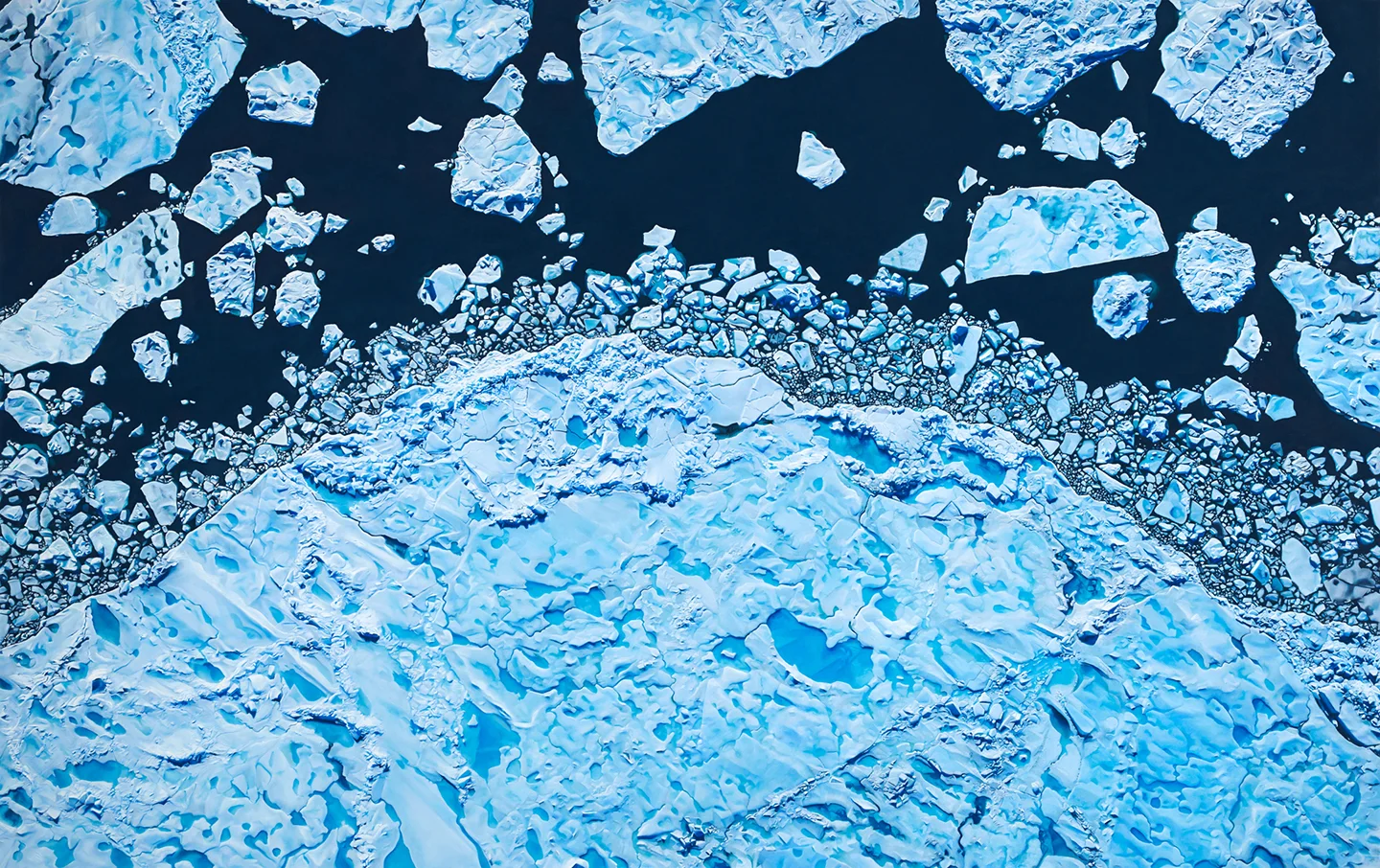

Zaria Forman documents the effects of climate change through large-scale, close-ups of ice formations in her pastel drawings.

Lincoln Sea, Greenland 2019 (source)

Mary Mattingly is a multidisciplinary artist applying a range of mediums and materials to explore the relationship between humans and nature.

Life of Objects from the collection House and Universe, 2013 (Source)

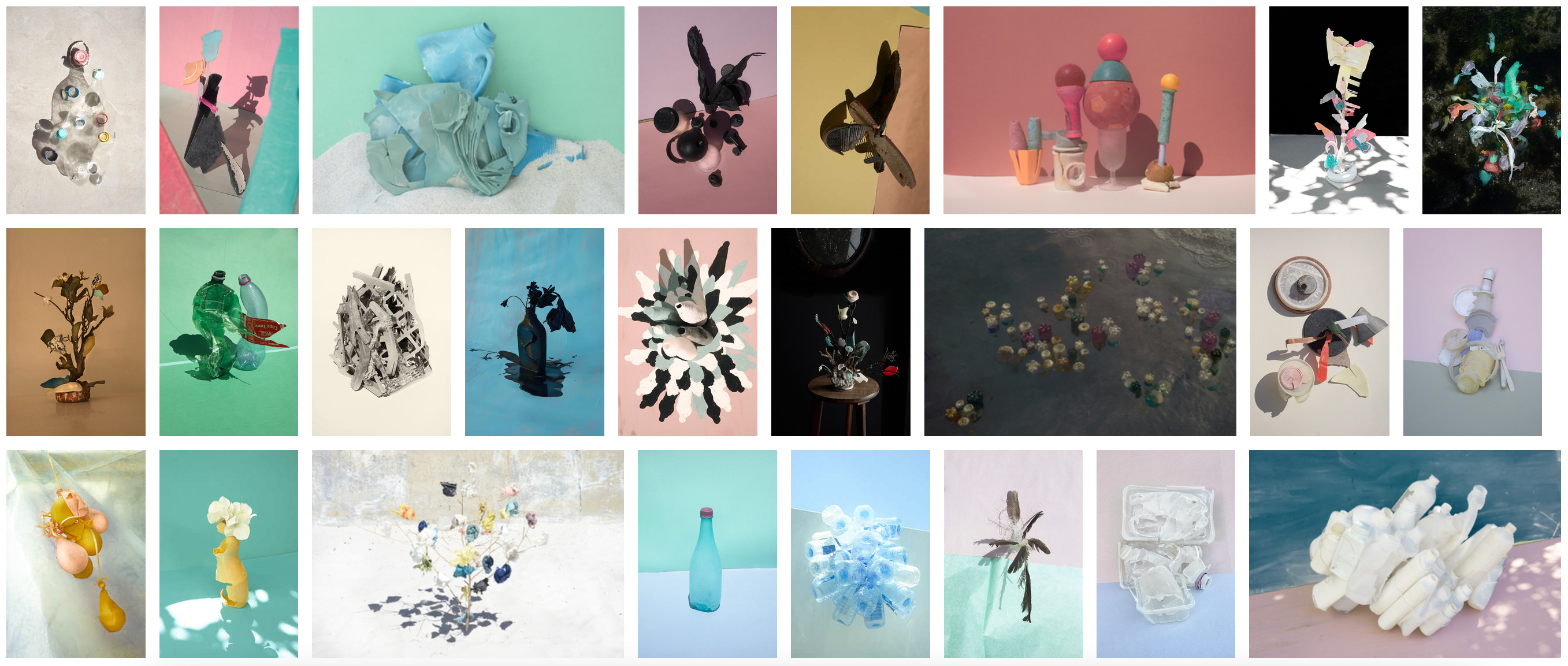

Thirza Schaap is a photographer who captures the different materials and forms of rubbish found in the sea or on beaches to create a deeper protest on consumption and the impact of it on the climate.

Plastic Ocean Project (Screencap, Source)

The soup protests have ushered more chatter on the urgent issue of climate change – and hopefully, that chatter can stimulate more significant conversation on how we, as a global community can slow down the effects of it. More generally, the history of defacing art for a cause shows the desperation that ordinary people face, it shows the lengths they will go to in order to hold governments and leaders responsible for issues that need to be addressed by constitutional change.

My point here is to illustrate the fact that messages can be conveyed in many different ways – the collaboration of art and activism can be way more powerful than their division. Art has the ability to bring people together and in times of impending catastrophe, voices are much louder in unison.