By Zoë Goetzmann (@byzoesera)

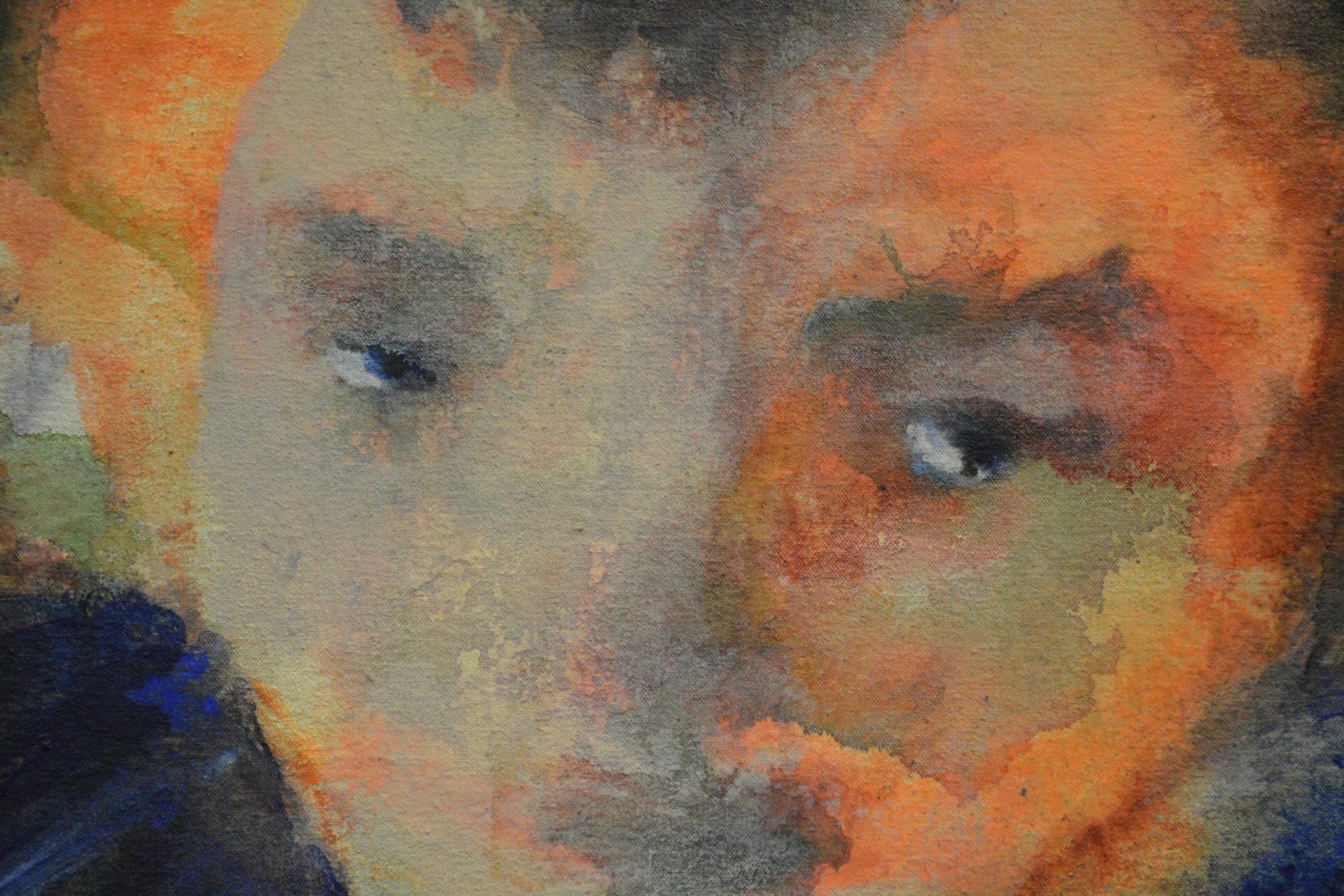

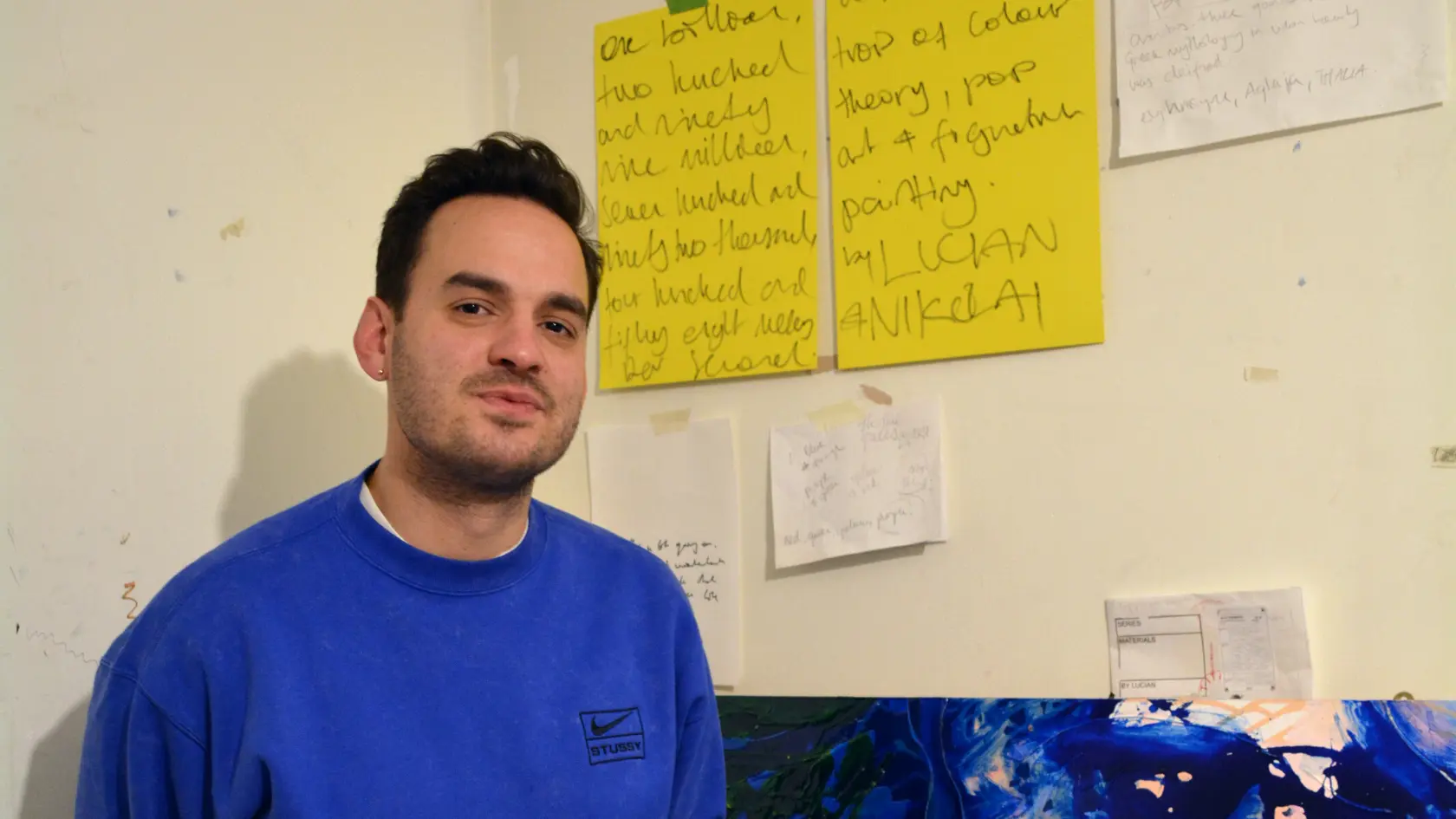

Interview with Anna Kolosova – Contemporary Artist

This week we visited contemporary artist Anna Kolosova (@annakolosovaartist) to talk about about her art and painting practice, her synaesthesia (the process of painting based on the senses, one’s surroundings, and this “5-D” world, Kolosova adds), mental health, music, finding one’s confidence, and how she navigates the traditional art and gallery landscapes as a professional artist.

Anna Kolosova graduated with an MA Degree from Central Saint Martins, and is an internationally exhibited contemporary artist.

She has shown her work in London, Milan, Düssledorf and Moscow. Her work has been featured in The Guardian, Cosmopolitan, and in Vogue.

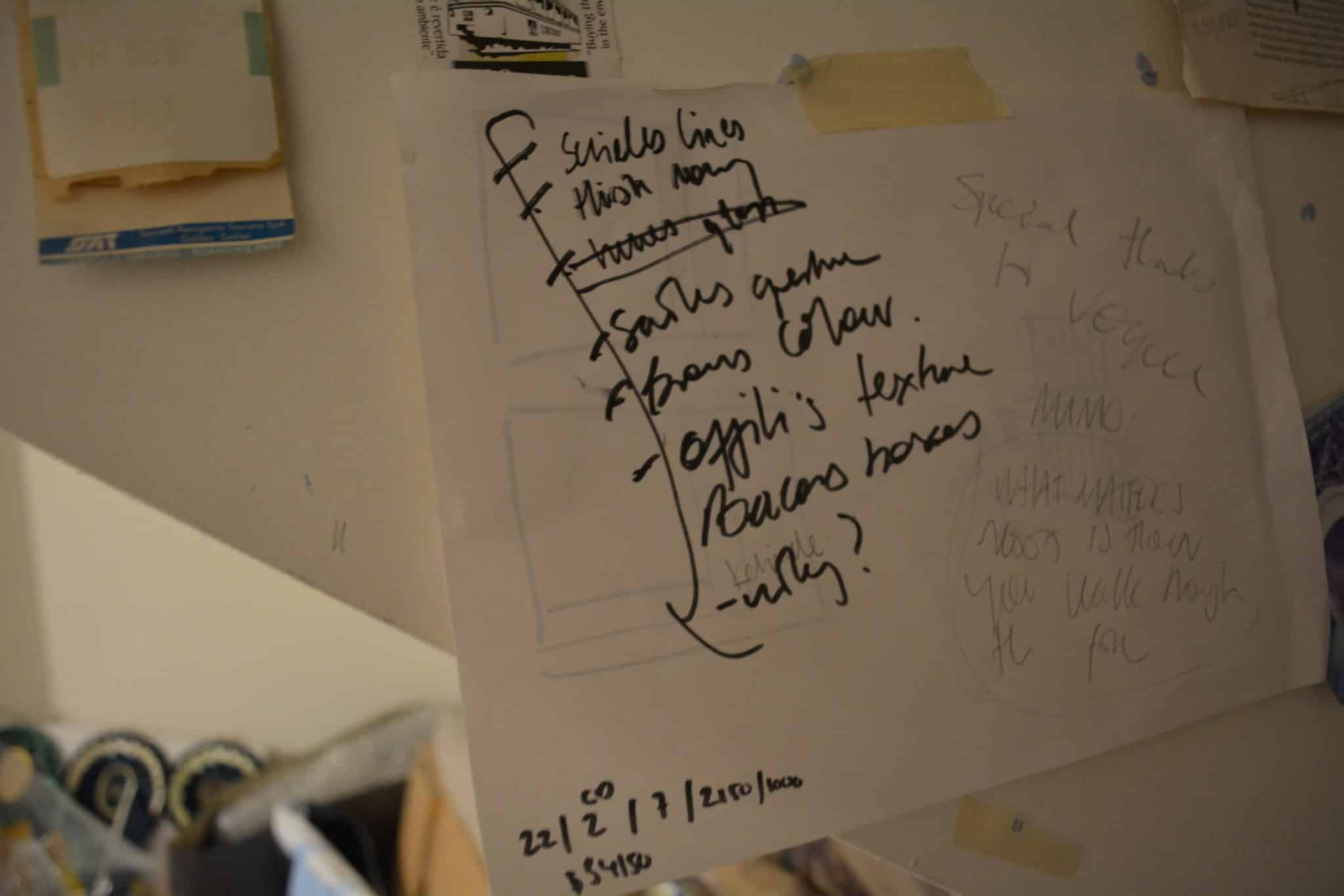

At present, Anna Kolosova is working on digital and NFT projects – exploring the depths of her painterly process.

Zoë: Hi Anna! Thanks so much for taking part in this interview with Cosimo Art Tours? Let’s start out with the first question.. How did you become an artist? What is your artists’ journey?

Anna Kolosova: Well, it’s pretty cliché. In my case, one of the clichés, is that since I was very little, I’ve always been obsessed with drawing and painting, usually drawing with markers and pen – not pencil, in particular – as a child.

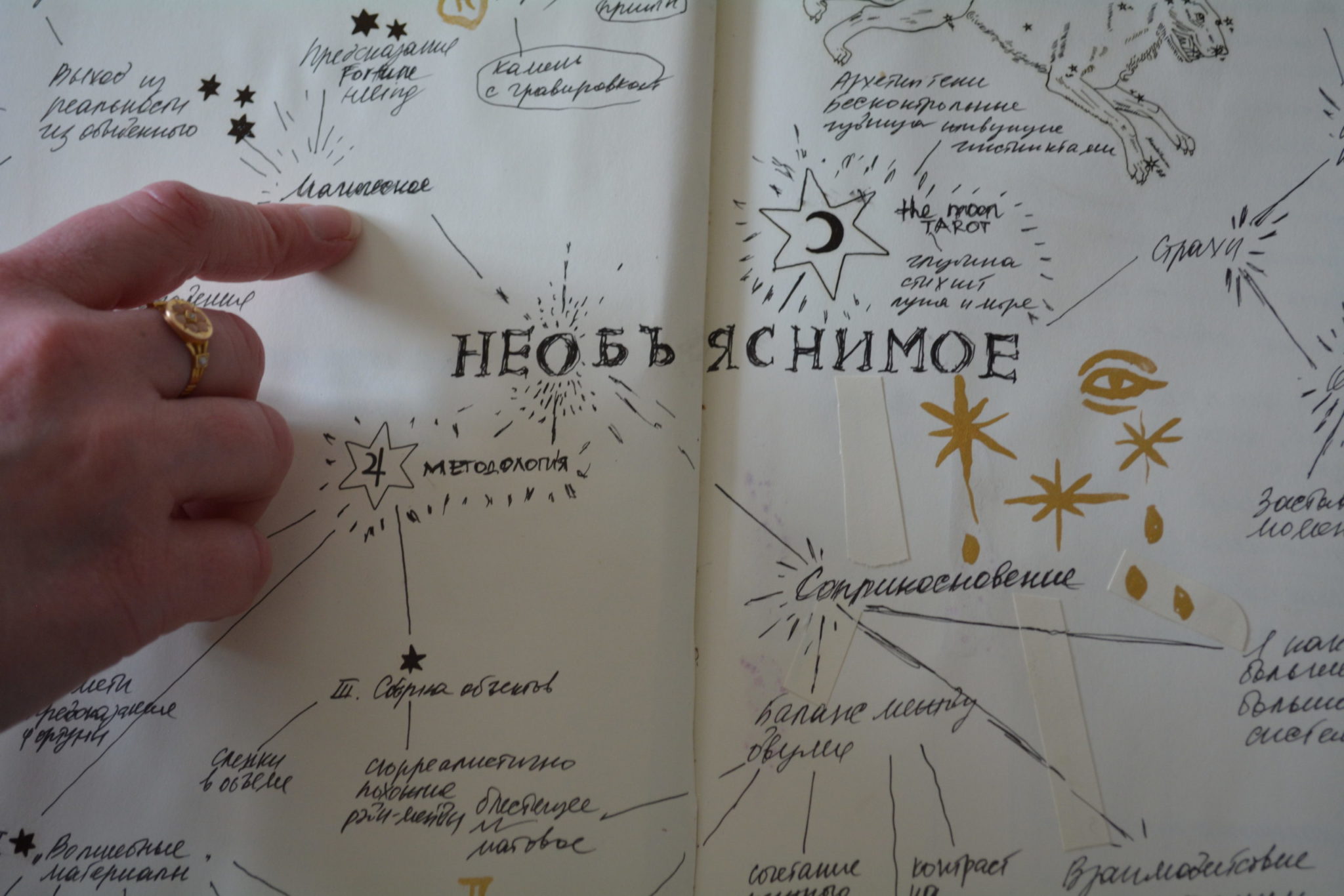

So, I like graphical, mark-making graphs. You could call it ‘graphomania’ – you know – it’s a thing.

My parents were both relatively creative. [My] father had his fashion studio. And they were also in education, and they had their own private school. And so, it was kind of like ‘an intellectual elite vibe.’

So, all their friends were artists, or people in the arts, or education or fashion. So that’s why they suggested I go to study art. In the first and last year, it was an evening school to prepare for the exam for a Russian school, named after [Vasily] Surikov.

There I studied Neo-Realism and Architecture, in Moscow.

Then my mother suggested I check out London for a more contemporary approach to Art Education. And of course, I was a teenager, I followed her advice.

And I came here to do some short courses at Central Saint Martins. I did three short courses. Quite a lot, but one was in Fashion Illustration, in Image-Making, just quite broad, different kinds of image production techniques.

And one was painting, I think. So, I liked how they made us think critically about our work and our methodology, and all that, in the UK.

So, I fell in love with everything I did education-wise here. I moved here to study eventually at Central Saint Martins.

Coming from a realism background, then going into collage and abstraction and sometimes more object-based ‘tableau’, painting in the expanded field.

Zoë: What were some of the differences between studying in art school in Russia versus in the UK or London? Was there a vast difference? Like what were the technical things?

Anna Kolosova: Right. Eye roll. As far as Russian art education goes, it’s very conservative and very technique focused. So you learn how to imitate life that you see in front of you – literally in front of you – not from a photograph, but from real life.

And you learn it the same way, more or less how they learned it, being an apprentice of, I don’t know, Leonardo DaVinci or someone. You learn how to measure everything, the proportions of the body of the skull, of the face, how to create depth in an image – physical (three-dimensional depth).

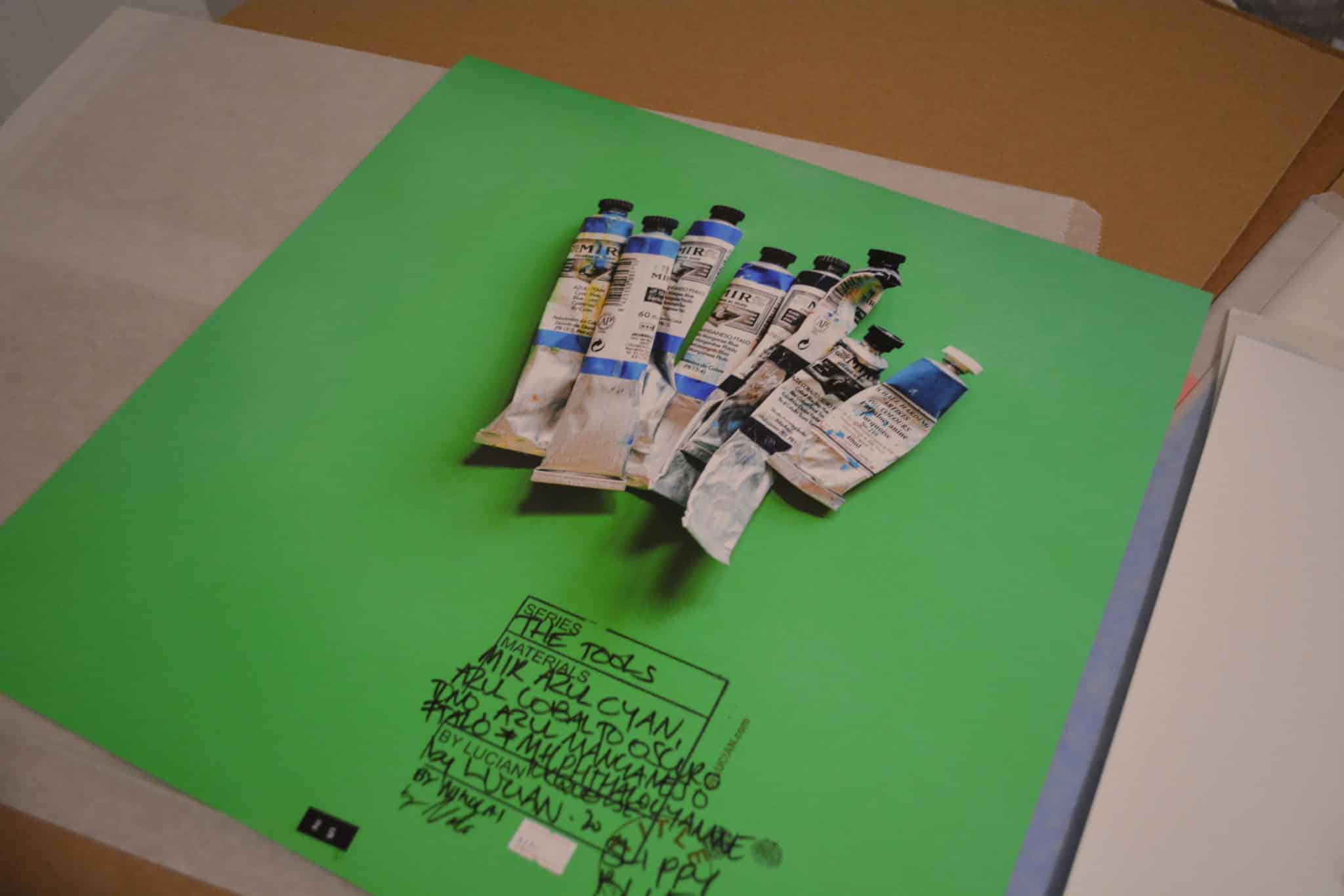

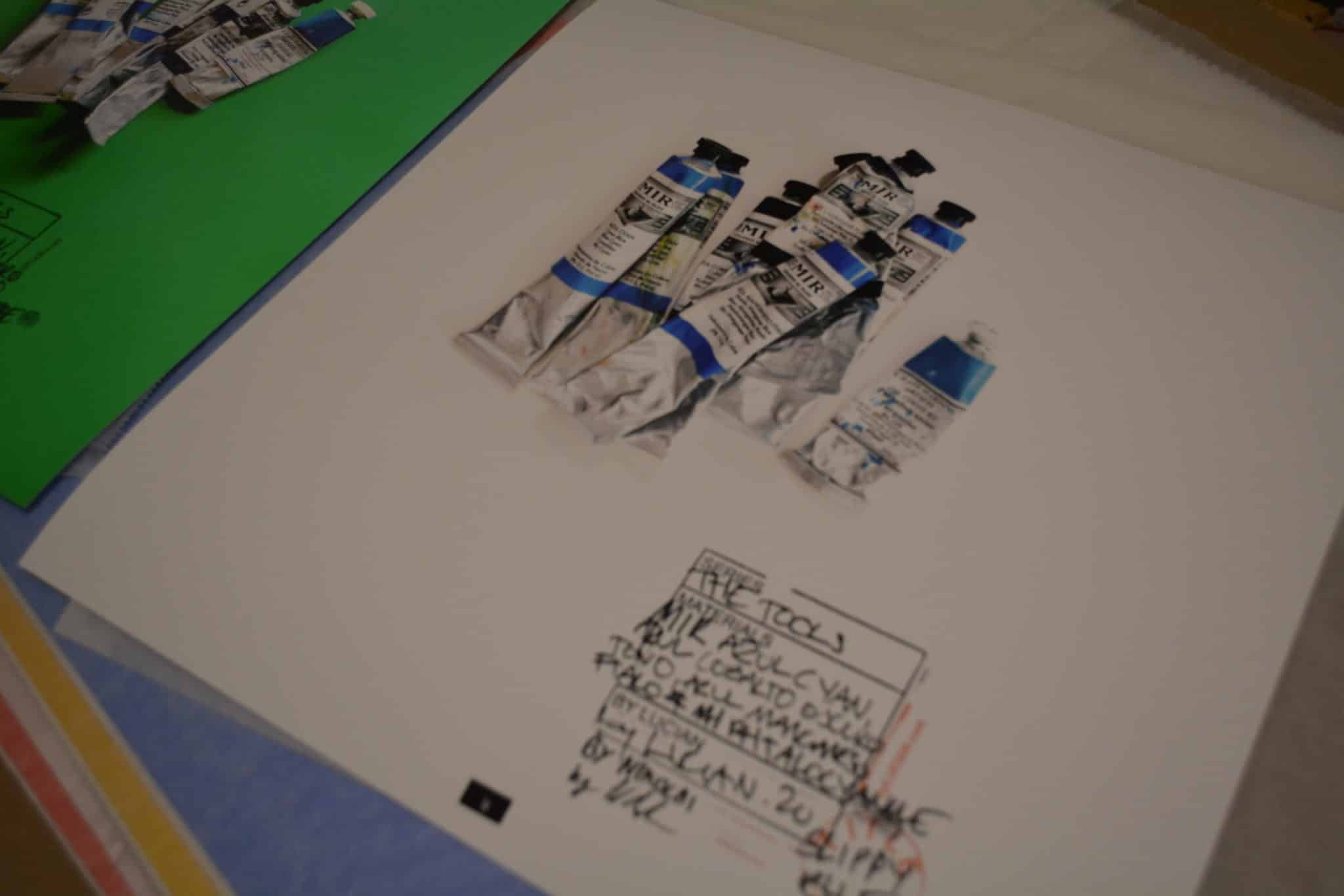

So how the shadow is cast, and you learn physics of colour and how to mix colour and you learn different techniques of painting and drawing with pencil, graphite, not charcoal that much actually, mostly pencil and egg tempera.

Well, because I took the architecture path, so we didn’t learn oil [painting]. We learned egg tempera, acrylic a bit, watercolour and [working with] pencil using just brown or black water colour to create with water basically monochrome, sort of like a black and white image – which is called “Grisaille” which is a French or Italian origin of that style. I did learn oil along the way also, just for my own sake.

It’s very different. I do not like it that much. They [Art Schools in Russia] don’t teach you much of contemporary, actually, at all any contemporary art or modern art history.

They teach you some of the old masters. That kind of history, but not even that much. It is more about just literally the technique, and you sit there for days and days and months and months. To make this image fall out of the paper or canvas, which is that realistic.

That’s why it’s called ‘Neo-Realism.’

Zoë: Was it good to have that foundation looking back?

Anna Kolosova: Yes, I believe so. Because you also learn how to construct the composition as well.

However, it ‘makes you think in space’ – that’s I think a quote from Tracey Emin, if I’m not mistaken, she said something like that. It’s very important to look, to sketch from real life. Because if you think differently about your surroundings, that can transfer into conceptual thinking later on as well.

Especially now that we have all this technology, such as VR [virtual reality] makes you think about it, which I’m now starting to use *spoiler* for my next upcoming project, potentially TBC.

Here in the UK, they teach you how to think and how to reflect, which you don’t get much of in Russia, unfortunately, because their people are very conservative in everything as we can see what’s happening right now.

So they teach you all the techniques, which they don’t teach you here, but then here they teach you how to think, but not the techniques. I’m glad I have a bit of both.

Zoë: It’s good to have a bit of both, honestly. You have the best of both worlds a little bit. When you studied architecture, was that something your family asked you to do and/or suggested?

Anna Kolosova Yes, we went with the Architecture path, because this style of realism they had was one I prefer.

There were a few pathways that one could have chosen. The others, they were learning oil and a freer kind of approach to painting. More free and yet very brown-based, [all] the colours. Less exciting, basically, in my opinion.

As far as Realism goes, I really like, you know, [artists such as] Van Eyck and [similar] Old Masters.

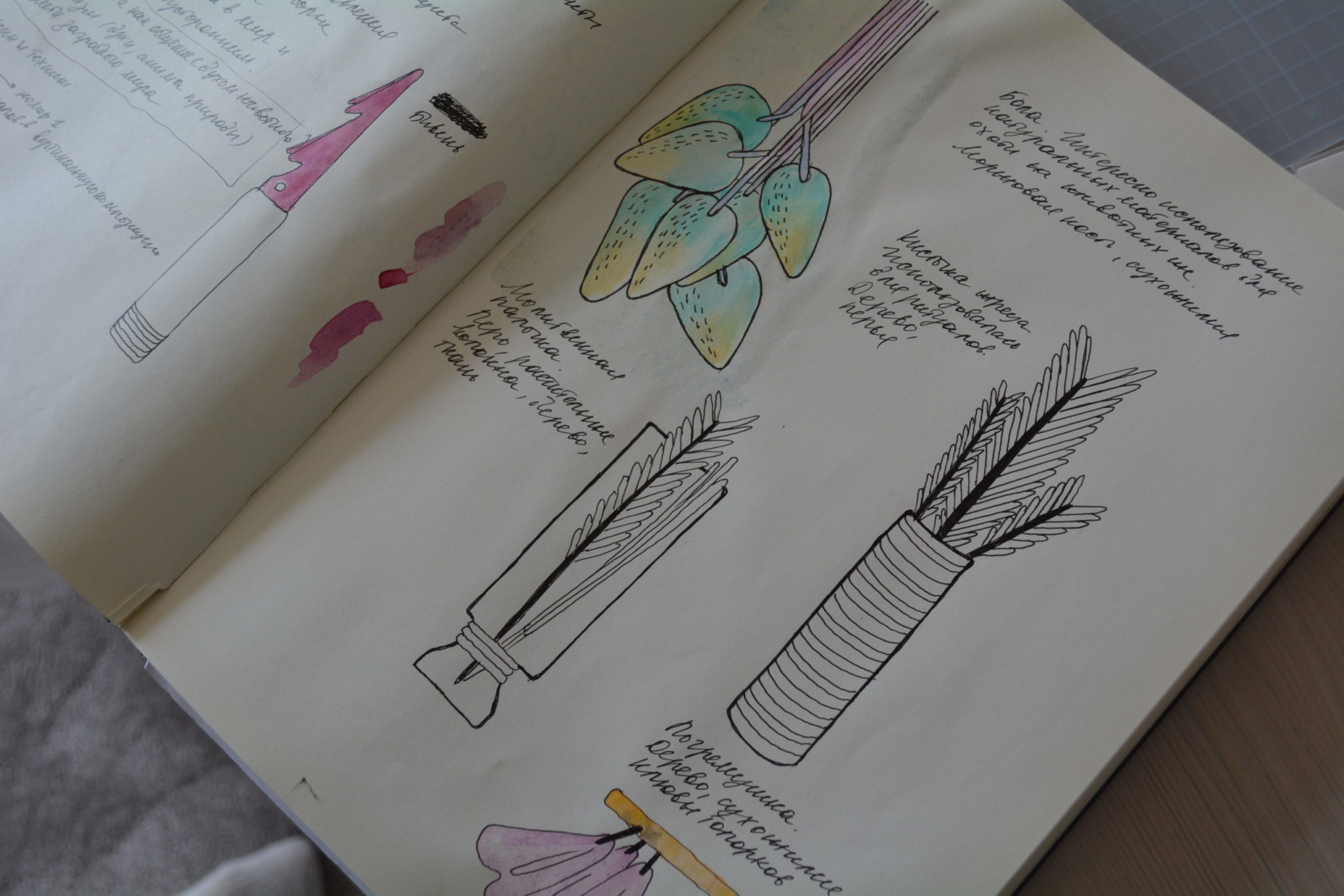

Because we used tempera. So [a] very old technique. And I kind of like it. Same as the graphics with markers and when you have to use the brush almost as a pencil to make strokes, almost to construct, you know, I mean, I’d have to show you how would that mean to create that same way as you used pencils for the shadow to add more marks in the same area to concentrate the contrast in that part for where the shadow is?

You do the same with the brush with tempera and it dries straight away and dries in seconds. You can already put new marks on top of it.

The previous marks are very linear and the contrast between the light part of an object, where it touches the darker background, and it’s just something quite fashionable or delicious about it. I don’t know how to explain it.

Zoë: That’s cool. This goes into the next question about your art practice and like the mediums and themes you work with: What made you want to choose painting in the end?

Because you said you studied three short courses at Central Saint Martins. What made you just pursue painting?

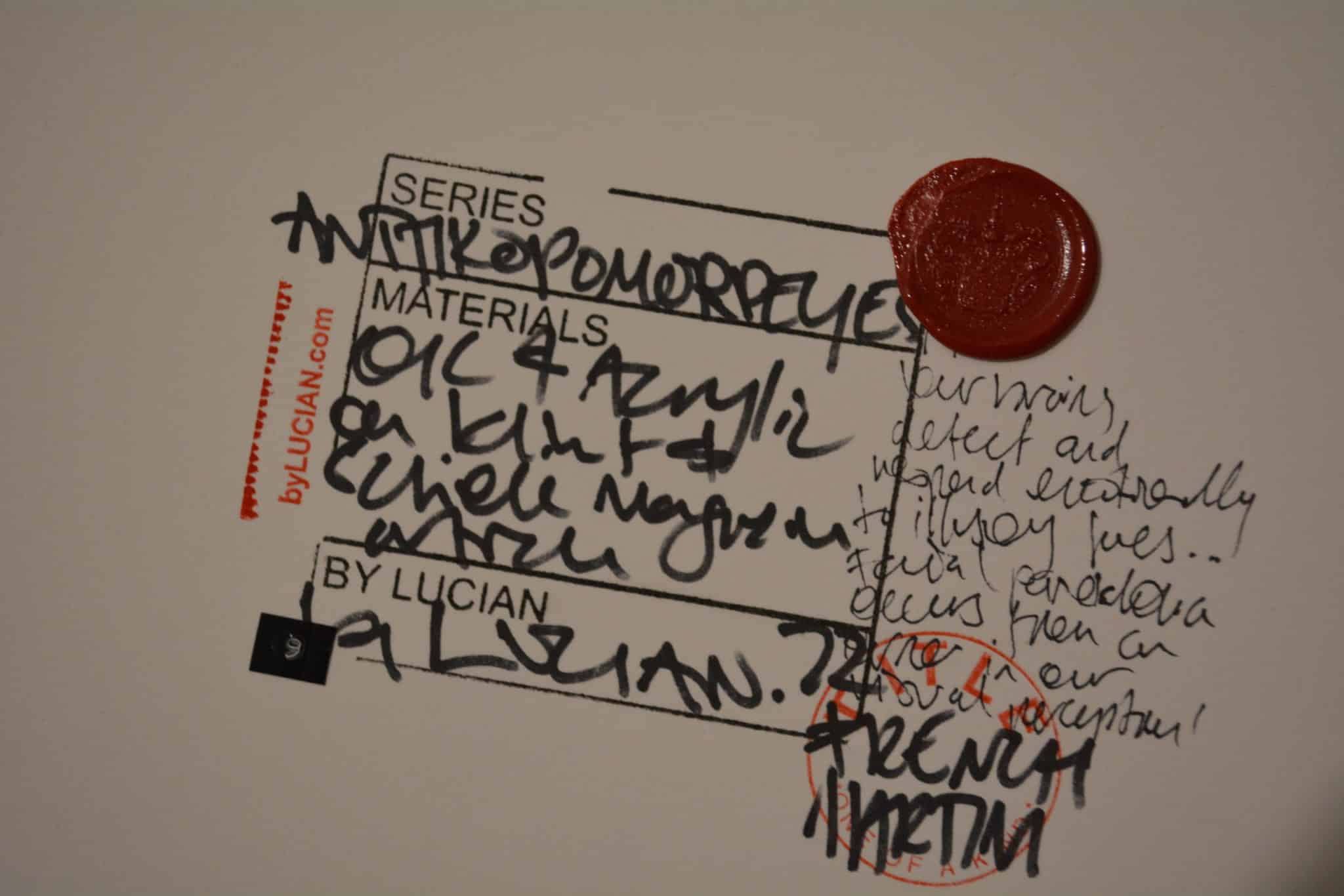

Anna Kolosova: Well, I pursued contemporary art and not just painting. I did collage. I did a little bit of video and performance, but yes, mostly painting.

So, I think painting is a state of mind. This sounds so cringeworthy. Painting is a state of mind – to me. Painting can be anything: ‘Painterly.’ Even when you look around on the street, like you know that Facebook Group: “Involuntary Painting” which has an art manifesto to it, (I’m an admin of it, I’m involved a lot) – so you can see images on the street that if you’re ‘an alien’ (for example) coming down to this planet, you would think that could be a piece of modern art basing on the algorithm of meanings of what creates a piece of modern art, for example.

And I guess I just have an eye for this for the composition and that’s why I can not not paint or not not not see things as paintings.

But I like to challenge these notions through using different mediums and going into more sculpture or more performance. Now, VR – who knows what will happen? You know? But I see everything as paintings.

Zoë: Would you be able to go into your synaesthesia? Could you talk a little bit about how your synaesthesia affects your [painting process and] how you see your paintings visually and your visual, painting practice?

Anna Kolosova: It’s interesting you asked me this question about synaesthesia in the context of what I was talking about just before, about ‘seeing,’ like a random splash of something on the street and it looks like an image made on purpose but it was not made on purpose.

So, for example, whoever picks out [a] certain compositionally constructed strong image – be it made on purpose or by accident – I don’t know something, like, like a rusty piece of metal that the builders left somewhere and then maybe it looks like the coolest abstract canvas, you know, that you could put on your wall.

But not many people would notice it, the beauty in that, and the value in that. They would walk by. But if someone chooses to see it as beauty, for example, as far as painting, it could be that those people have a different kind of vision [or] inner vision.

Also makes me think of this philosophical concept of Daniel Dennett – a contemporary living philosopher, he talks about this term called: ‘Qualia’.

It’s complex. It’s about images. And it’s about like, for example, if you see an image, he gives an example: ‘it’s an American flag, but all the stripes are green instead of red.

And he goes, “Well, do you do you see the green flag or the red flag?” You see the green one. But in your head, you also see the red one like the way it’s always been, you know? So that’s ‘Qualia.’

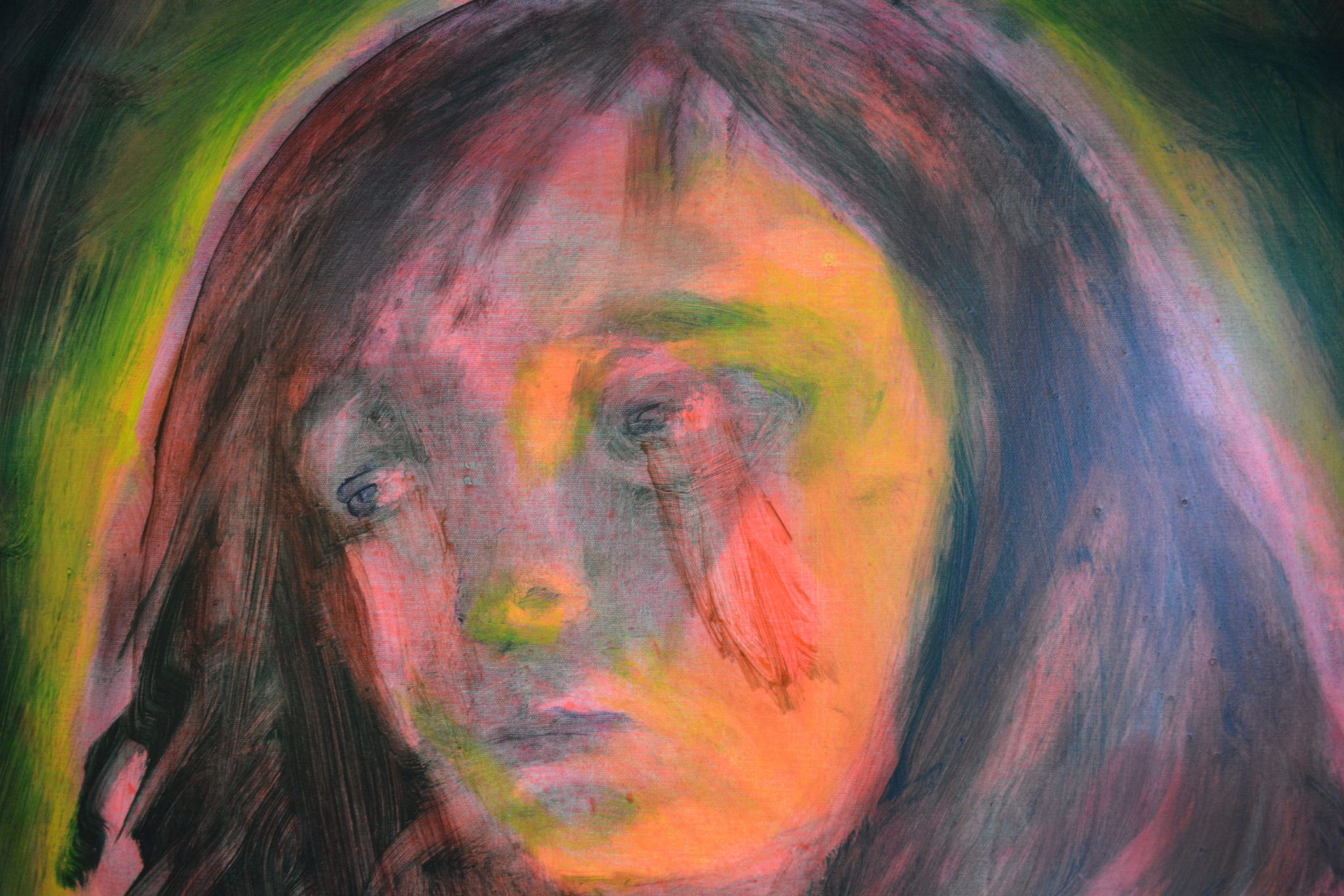

So, in synaesthesia, for example, when I see numbers or letters, I see them the way they are, but in my head, they also have a different colour automatically. Always the same. And the sounds have a colour and shape (sometimes yes, sometimes no shape).

The answer is yes, it has an impact on how I paint. I think I’m trying to paint from reality that is in my head. Because they say, there are some theories that synaesthesia comes from 5D [Fifth Dimension] – they say, you know, all the spirituality that we know of comes from.

Because there’s other dimensions beyond that, but we just don’t have any access to them much yet. And basically, when I see visions for sound, I try to paint something similar to what I see. It’s like painting from life like I used to with Realism.

But the still-life is in my head. Except it’s not ‘still’ it’s ‘moving.’

Zoë: What other themes and mediums do you work with in your painting practice?

Anna Kolosova: Mental health, spirituality, relationships – kind of romantic relationships. Human nature, but that’s similar to mental health.

Zoë: How do music and spirituality affect your work? How do you bring that into your artistic practice? What music do you tend to listen to when you create? You used to make dancing videos on social media …

Anna Kolosova: Music? Well, because it’s always been a big part of my life as well. Both literally playing an instrument and recording songs and going to singing school.

But I wasn’t as good at it as I was at painting. I had to choose one to pursue it more deeply. So, I went for this, but I obviously still listen to a lot of different music.

I love discovering new music. I always spent, you know, effort to discover it on SoundCloud and other platforms and going to music events, both classical and electronic, and IDM, which is ‘Intellectual Dance Music.’

I wouldn’t call myself a connoisseur.. But ‘a lover of music’ and ‘an explorer.’ And I always date musicians … [both laugh].

Zoë: How does listening to this type of music feed into your creative process?

Anna Kolosova: It depends. Sometimes I paint to the music and sometimes it’s just on in the background. There are times I don’t use music.

Very rarely. It’s not as pleasurable without music, as it is with. Because music makes it easier, not easier, but just adds a different dimension to ‘zoning out’ whilst I‘m painting.

Zoë: As you said: “Painting is a state of mind.” So, I don’t think that’s cheesy, at all. Artists have to be in the state [of mind] and you just ‘zone out’ and block everything out.

Anna Kolosova: When I said: “Painting is a state of mind,” I meant also the whole lifestyle. And literally: where you go, what you listen to, what you wear, with whom you collaborate. Everything.

Zoë: Onto the bonus questions that we ask everyone: What do you love most about being an artist?

Anna Kolosova: I love the lifestyle. I love that I can professionally ‘create.’

And part of that process is going to look at other people’s work and museums. And, working with other creatives, as well, and getting inspired.

But yeah, I think sometimes my paintings express more of myself than I can even do so myself, without painting. Sometimes I think my paintings are cooler than me!

Zoë: I’m writing that down. That’s also a tee-shirt! [laughs].

Anna Kolosova: When I was a kid, I was very shy and socially in-equipped at all. And expressing myself was the only way to escape from that reality.

And I was always expressing myself 24/7 even then. So, I find that, well, I don’t know exactly what it is, but it helps ‘my ego’ I guess.

Zoë: As an only child [which I can also relate to], you have to live in your imagination, most of the time …

Anna Kolosova: So, yeah, I guess sometimes, I was happy to be by myself. And other times, I was also very lonely.

So, depending on the day, I think, because my parents were always very busy and doing very cool things.

No doubt. And other times I was actually not willing to go outside. Like I never went outside. I was always alone by myself drawing, playing with my dolls, whatever else.

And whenever I would have to, you know, perform or something like that, dress up, it would empower me always.

So, I think it’s the same now. Not much has changed… That when I paint I feel most empowered. I feel sexy. I feel most developed as a human being. But I feel sexy not as a woman, but as a human being. Or part alien in this human experience.

Zoë: Anna’s not from this world [laughs].

Anna Kolosova: I don’t think any of us are, in the arts! No.

Zoë: Onto the more challenging questions: There’s a lot of things probably in the art world you would change, what is kind of one thing or your least favourite [thing] that you’d want to change in the art world?

Anna Kolosova: I don’t like to be under pressure, too much, to have to create for money.

That’s the only thing. I like deadlines when it comes to putting on exhibitions. But whenever it concerns any financial aspects of this process.

I do feel the opposite of ’empowered.’ Whenever it doesn’t work out in my favour. When it does, of course, I feel great.

So, it depends. Because creativity shouldn’t be limited to the financial aspects.

Zoë: That’s helpful for us as a platform, because we’re trying to empower artists and help them be able to sell and give them the confidence to do so.

Does the ability and guarantee to sell work provide you with a sense of stability? Business-wise, is there anything that helps you ease this anxiety?

Anna Kolosova: Anything that pays me every month would give me [that] peace of mind.

So, for example, in Norway or France, they give grants to artists, just because… it doesn’t matter on their merits, I don’t think.

I think there should be companies sourcing money somehow to crowd-fund and/or through donors, just giving out money to anyone – doesn’t have to be large sums of money – just anything that an artist can receive every month, even if it’s 200 pounds, doesn’t matter.

At least you know that you have it every month and you have like a budget for art materials or anything like that.

Because if you don’t know whether you’re gonna receive money the following month, you are less eager to buy new canvases and produce more or something like that.

So, of course, yes, networking opportunities, to meet dealers, collectors, patrons. If I invest in a solo show and then I can’t afford rent next month and end up being, you know, like a squatter, homeless or whatever else.

As most artists are facing these issues, or otherwise they have to commit to a full-time job, but, I mean, I want to enjoy life. I don’t want to be ‘a slave’ to ‘this non-working system’ where creativity is NOT a must, for some reason.

Zoë: I think that’s helpful. That’s what we’re trying to do too. At the same time, bringing two worlds together: the traditional and online space, but then also ‘break the gallery system’ and empower artists who want to sell and so that they can actually sell their work and that people can support them.

This goes hand-in-hand with the previous question: Is there one thing that you wish that people knew about being an artist? Can be the financials or besides the financial aspects?

Anna Kolosova: I suppose the one thing is: validation.

An artist shouldn’t feel like they need validation. They should try to be happy with their progress. It’s also very difficult to be happy fully with your results as an artist, because there’s always room for improvement.

No matter how good the piece is. Well, it’s kind of one or two things in one, and when you get multiple rejections from institutions, or you know, gallerists or other artists, if they disapprove of your aesthetic, for example, it hurts.

You shouldn’t be discouraged. That’s the most difficult part. I think for every artist, because eventually you do find your niche(s).

Zoë: That’s me as a writer. You’ll find a publication and/or a gallery that likes you or your work [who wants to print or exhibit your work]. Another woman artist, I know, did note that there’s a pressure for women artists to always have a perfect portfolio.

And for men, they can – from her experience – submit their portfolios as it is. Men have more of this ‘false confidence,’ where they just say ‘just look at it’ [some male artists, not all male artists].

What advice would you give to emerging artists who want to choose this pathway or is there any advice that you would give, creative-wise and/or business-wise?

Anna Kolosova: So, at art school they don’t teach you anything about sales. When you leave school, you might need to become a receptionist or unless you have a trust fund then you’re fine.

But if you don’t have a trust fund, you need to like ‘hustle.’ You need to have a plan of action, which I still don’t have much, but I do things differently myself. I try to kind of go with the flow. And eventually I kind of get there, but it’s a longer road.

I could have reached what I wanted, by now. had I been more strategic about things, and they don’t teach you this strategy at University.

Unless you’re studying art business. So, this should be taken into account that they need to find that info by themselves from books, articles, courses, workshops, talking to other artists, curators.

Have a strategy in place by the end of their University if they decide to take the path of art education, because otherwise, you stumble upon a lot of difficulties.

You don’t get the desired result in your life, or you get surprised, because you were told it’s ‘like this and like that’.

Actually, no… It’s very hypocritical, the whole system. If you go by the textbook, it doesn’t guarantee you anything.

And a lot of people who succeed academically, they end up not becoming artists. Actually, I’ve noticed from my personal experience, they ended up doing something else.

Zoë: That’s why I always ask people what their ‘Artists’ Story’ is because usually everyone who’s in the Arts did something creative. Everyone did that.

People ask, “are you an artist?” And my response is always: “I think everyone started out as an artist, at one point in their life [or earlier on in their life].”

Anna Kolosova: I guess my advice would be: to just know that it’s not going to be an easy road. Most likely, unless sometimes, I guess.

So, because you always have to balance between: ‘what your heart wants and what this three-dimensional matrix wants.’

Zoë: What is in store for you in the future? Art-wise?

Anna Kolosova: Exploring the digital realm, NFT’s – we [Anna and her collaborator] are planning to launch a collection that we already made last year, but there was a dip in the [crypto] market. So we’re waiting for a better time to actually sell it.

And now we’re working on another project which will combine elements of video and digital graphical elements TBC.

Zoë: What do you like about NFT’s?

Anna Kolosova: I like that it has an element of freedom. Creative freedom. So with something I can’t do with physical painting,

I can do there [in the digital landscape]. Because it can encompass ‘text floating around an object with sound’ that the painting cannot do.

Zoë: And then, looking back, what advice would you give to your younger self, aside from ‘having a plan [or strategy]?’ Is there any other specific advice you’d give to your younger artists self?

Anna Kolosova: Be more confident. I missed out on so many opportunities. They were throwing themselves at me. I could be really famous right now.

Zoë: With galleries or with making other art world connections?

Anna Kolosova Both. I would send an email, or receive a reply, and [someone would write back]: “Oh, contact my office, set up something with my PA.”

I would email the information, [sometimes receive] no response and then I would get insecure [and think], “they probably don’t want me. I’m not going to bother them again. And that’s it.”

Zoë: What would help with your confidence? Is it just internal?

Anna Kolosova: Yes. Like my artwork was good already then, but I didn’t think I was good enough. So, nothing happened.

Zoë: That goes with what you said about the validation.

The validation should come from within you. I know how difficult art school is. They put you through a lot of stress to become ‘the best.’

And I think that’s like a positive and like a negative, a little bit. In that traditional sphere, they put a lot of pressure on artists, when we’re supposed to celebrate art.

It’s hard for artists to handle that stress. They’re not always built for it, so artists have people [like gallerists, agents, dealers] to handle it.

Anna Kolosova: Even when you get a big opportunity, and if you’re still quite young, it’s you against the world suddenly. You don’t know your limits, your boundaries, your skills, your advantages, [your] disadvantages.

You don’t know yet who you are. So, even if other people think your work is good, or that – you as “a professional” are good, you might still find that you get paranoid and insecure.

Zoë: The reason why it’s hard for artists to ‘think business-wise’ is just because to make art, there’s a lot of emotions that go into it.

Emotions don’t really translate into business. It’s a little bit hard to be vulnerable, which is a benefit for you [as an artist].

For you as an artist, you have assets that people in the gallery world don’t have. They don’t understand.

Anna Kolosova: Yeah, and the fear of rejection is just insane but I’m trying to overcome it with therapy and coaching and self-work and everything, but it is very difficult.