By Lauren Parsons

Exploring Creative Visions – Interview with General Blimey

Phil (a.k.a General Blimey) is a Birmingham-based illustrator. Through his work he delves into the essence of the everyday by peeking through windows or vacant doorways in local establishments, as well as refashioning the identity of familiar objects.

Creating art that reflects what he sees everyday has always been a preoccupation for Phil. As he explains, “I had this idea for ages where I’d film a spot, keeping the camera dead still. There wasn’t much that took place, a cloud might float over and change the light or cast a shadow.

“But that’s where the idea of the stage comes in – nothing is happening in this scene but you know it has done, or it will do. Someone might be sick there or someone might propose there, or it could flood.”

“I am more bothered with where things have happened, the spaces that things could happen inside of rather than the actual happenings themselves.”

Whilst Phil’s art underscores the significance of the stage above its actors, much of his inspiration is derived from human endeavour.

Very soon into our conversation, he explains how the music he listened to growing up not only provided a backdrop to his daily life but also played a significant role in shaping the art he created.

Bands like Blur, The Jam & The Kinks. All Britpop greats who used a combination of humorous, satire-laden lyrics and unpolished sounds to broach many of the social, cultural and even political issues of their day. Garnering them considerable popularity amongst the working class & youth cultures in Britain around the 1960-90s.

Over 40 years later, they were providing a soundtrack for Phil growing up in a largely working-class suburb of the Black Country in the 2000s.

Today, their influence is still indelible in Phil’s art. In the same way his favourite bands used the medium of music to provide a sort of cultural commentary, he uses art as a means of better understanding his own reality. Every choice he makes, from his artistic inspirations down to his own subject matter – is based on how well he can relate to it.

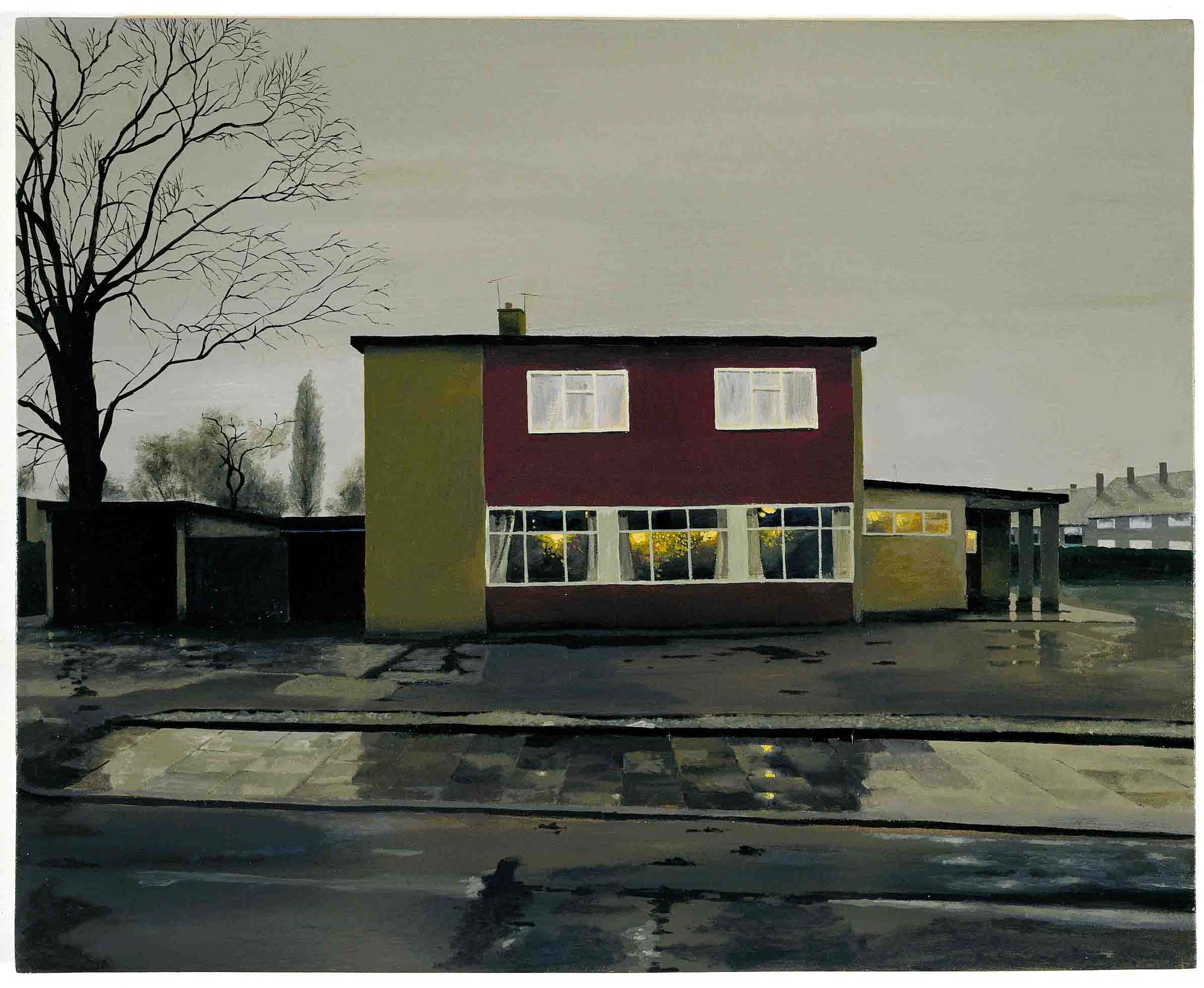

Take for example, the work of one of his artistic inspirations George Shaw, who captures ultra realistic urban landscapes in minute detail.

“He uses model aircraft paint, which means that his works are really fine, and can capture every last detail. He can show if it is a particularly muggy day or if it has just rained. The places he depicts feel very familiar too – like streets I’d walk down on a daily basis.”

Using these techniques Shaw perfectly renders the way streetlights bounce off wet pavement, how this reflects back in a window on a particularly grey day, or even the feeling of warm, heavy air.

Many of his works depict the streets of Coventry – a city whose suburbs are emblematic of many regions in the UK, marked by the prevalence of Brutalist structures stemming from a surge of post-war reconstruction projects happening across the country from the 1950s through to the 80s.

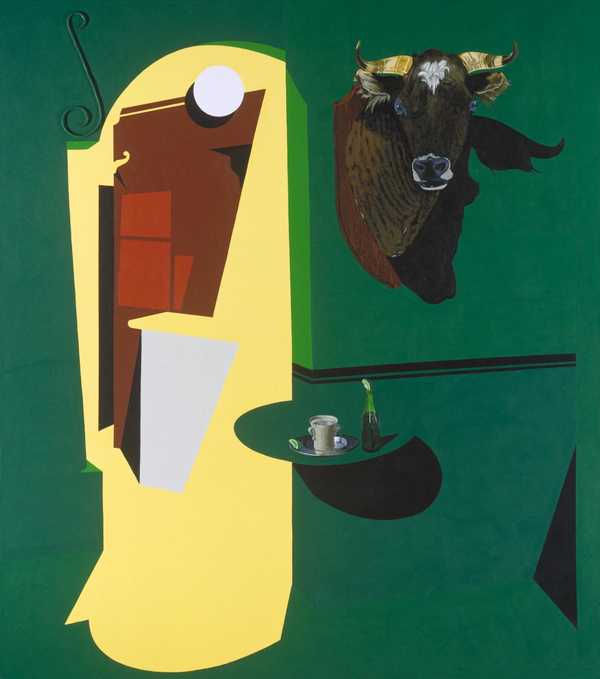

If George Shaw captures the exterior of everyday life, Patrick Caulfield, whose techniques have had a big impact on Phil, brings the focus inside.

“Caulfield is a big influence in terms of how I present the subject, especially in how he takes a similar photographic approach.”

It is clear to see Phil’s affinity with Caulfield’s prints and paintings. Whether it’s in his application of bold colours on almost photorealistic yet consistently simple interior scenes. Or in how he plays with the light contributed by an open doorway and the possibilities of what’s lurking around a corner.

Phil explores similar ideas in one of his most popular commissions, the facade of Snobs. Even the mere uttering of this hallowed institute will cause many people in their twenties or thirties to shudder.

However, this is a club with a long history, having been visited by generations of West Midland-ers. It is an iconic building (and wall of faces). As well as a vital step in every local Gen-X/Millenial/Gen-Z’s coming-of-age story.

Phil struggled with the decision to create the piece in what is, an age-old struggle for artists juggling commissions with their own art practice. He felt as if he was plucking the Birmingham artist’s equivalent of ‘low hanging fruit’. Feeling as if “It was too obvious – so obvious it felt like I was creating click-bait content.”

Biting the bullet, he ended up creating a piece which proved a popular print amongst his wider community – and with that, more versions of the original commission have followed.

What made the piece popular is that, for locals, it felt familiar, almost nostalgic. Viewers were transported back to old memories just by looking at Phil’s Snobs, with its windows crowded with loud club posters.

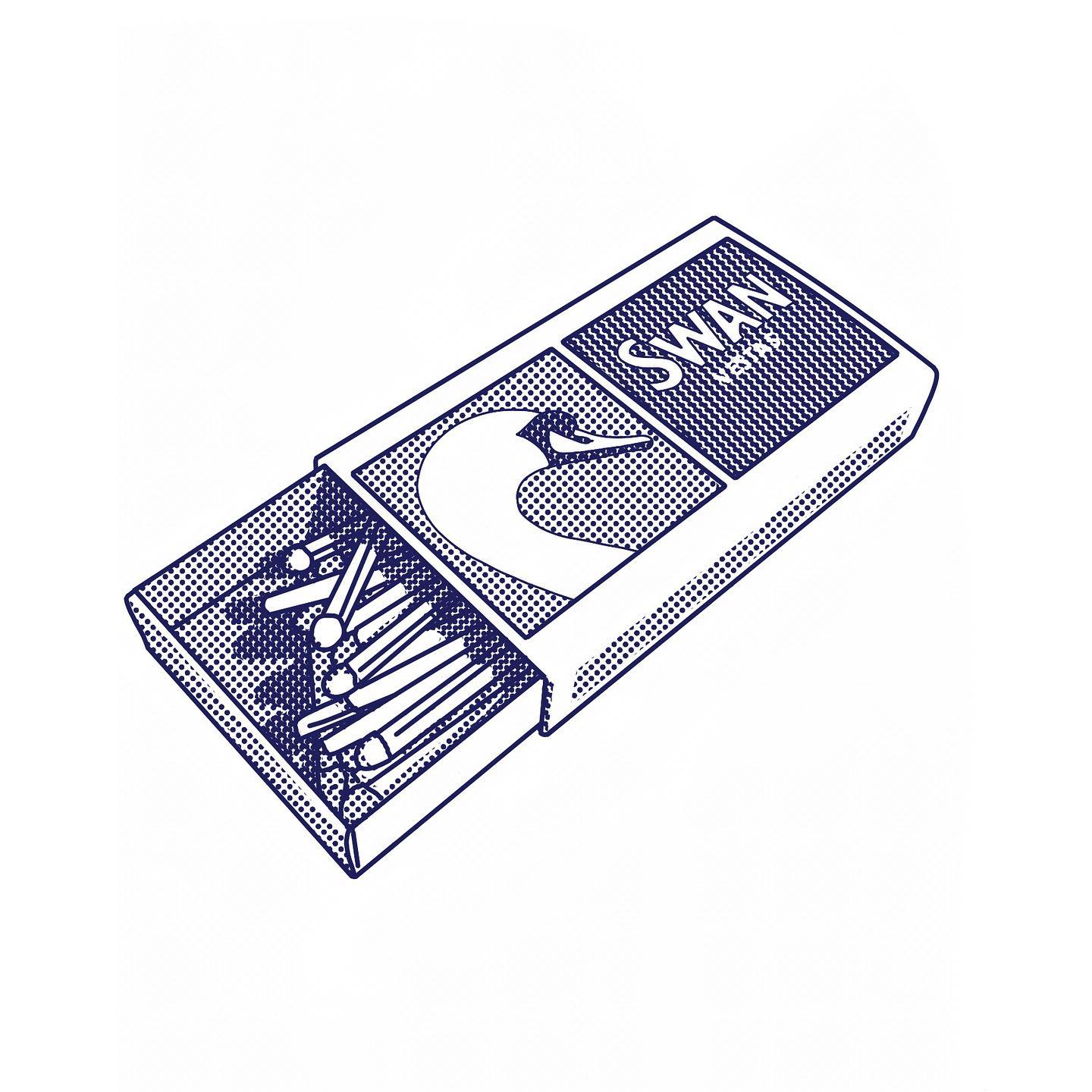

Phil’s portfolio doesn’t stop at buildings. Some of Phil’s more recent, and equally eye-catching works are inspired by tattoo flashsheets.

One that initially caught my eye featured a Tunnocks Caramel Wafer – a chocolate caramel snack created in 1947.

You can still find it in the snack aisle of any supermarket today, in what looks like the same wrapping it’s always been in – an iconic red and gold striped foil.

However, within Phil’s print the Tunnocks Caramel Wafer is no longer a chocolate bar. Rebranded, it sits beside its newfound comrades a cafetiere, a candlestick & a lucky cat (Maneki-neko), amongst other objects.

Recolouring the objects in a dappled, inky blue, Phil relinquishes them from their original function. They can now be anything – part of a tattoo flash-sheet, a collection of postage stamps, a Lego construction manual or what Phil refers to as ‘the ingredients of your day’.

Whether it’s through his “Rear Window-inspired” approach to buildings, looking beyond their initial flatness to peer into a window or catch the last glimpse of a shadow rounding a corner. Or in his collections of everyday objects, regrouped and repurposed with an identity that exceeds their functionality.

Phil’s art seamlessly balances between the realms of the familiar and the unique. Paying homage to the everyday by, as he explains it: “applying the same lens that you see a beautiful sunset through, to the handle of someone’s favourite cup or the roof of a building they walk past everyday.”

As the pioneer of the Super Ordinary Life movement, Yasumi Toyoda puts it: “there’s [just] something unexpectedly addictive in seeing the familiar through fresh eyes”.

You can find Phil’s work here.

You can follow him here.