By Zoë Goetzmann

Interview with Fiona G Roberts – Inspiring Art Journey

This week on Cosimo Studio Tours, we visit artist Fiona G Roberts’ studio located in Bank at The Koppel Project in London.

In this interview (which you can listen to in full here) we delve into a variety of topics ranging from her latest body of work, women artists, as well as gender inequality in the art world (running through the statistics as well as the stagnant two percent of top-tier female artists who sell at art auction).

Fiona G. Roberts holds an MA in Painting from Wimbledon College of Arts – University of the Arts London where she received the Vice Chancellor’s Scholarship.

She completed two years at the Turps Banana Painting School (2019-2021). She has participated in multiple group shows in London and in the U.K., including Dentons Art Prize Exhibition, 2018, Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize Exhibition, 2018-2019 (Runner-up and Winner of Staff Prize), ING Discerning Eye, 2020, Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, 2021, ‘We Are Such Stuff As Dreams Are Made On’ at Aleph Contemporary, London, 2021, ‘Two Doors’ at Tart Gallery, Winners: Award Winning Artists, Mall Galleries, London, 2022.

She was also shortlisted for the Ruth Borchard Self Portrait Prize 2021 and the 2021 Figurative Art Now Exhibition where she was awarded a Mentorship Prize.

Zoë: Thank you so much for being here, Fiona. I was excited to delve into your work. I love sitting in the studios and looking at everyone’s paintings.

To kick things off, can you tell me about your artist story? Essentially, what was the journey that led you to becoming an artist?

Fiona: I think the honest answer is, I’ve probably always been an artist. I think if you’re an artist, you’re just compelled to make things and to do things and to make art.

And so I’ve always done that, really. And it was the thing that made me happiest as a kid or even throughout my whole life, really.

But my parents thought that going to art school wasn’t a great idea. So I did other things first.

My first degree was from the London School of Economics, and I did another degree after that.

From there, I went to Goldsmiths, actually. And then I was a research fellow and academic research fellow and a teacher. So I’ve done lots of things.

But all the time, I was building up my art practice. I never stopped doing art. I was always making art. And eventually, I did my MA in painting at Wimbledon, University of the Arts, London.

That was in 2016. I got a scholarship to do that, which was really brilliant. And I graduated in 2016. Then I launched myself as an artist after that.

Zoë: Can you tell me a little bit about your paintings and your practice?

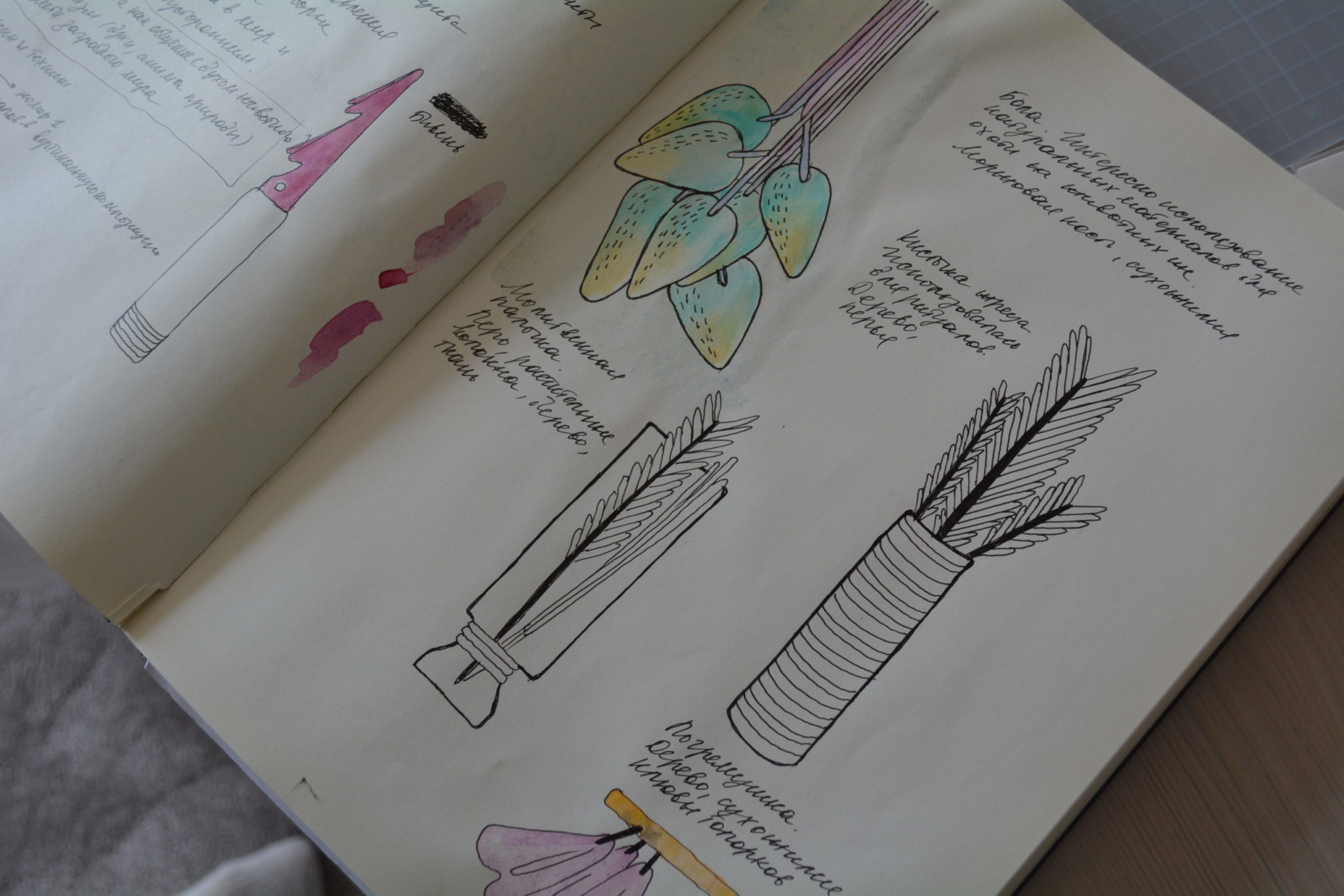

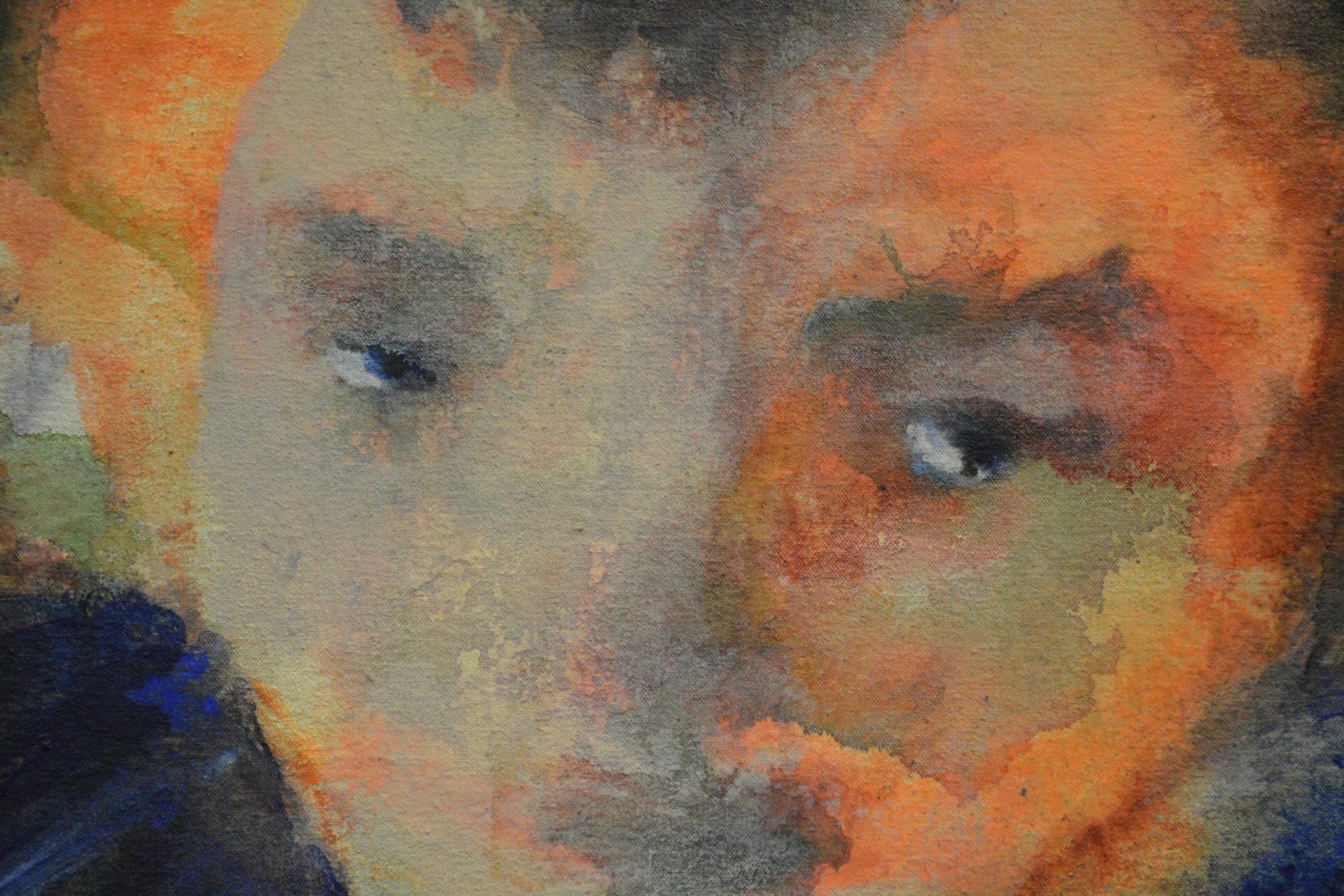

Fiona: Sure. So, I’ll tell you about the practical aspects first. I work in quite a broad variety of mediums, mainly oils on board or canvas, sometimes on perspex.

I also use acrylics sometimes. And I also use inks quite a bit. And whatever I’m doing, whether it’s with across all those mediums, I’m doing the similar thing, really, which is sanding down the medium and using lots of layers.

So I’m building up layers, and yeah, lots of watery layers. Although the medium is quite different, I’m doing the same thing.

Zoë: Where did that thinking and process go from that this intention to do that sort of technique?

Fiona: I think it’s just something, if I’m honest, that has developed over the years. You know, a lot of art is about trial and error. In fact, so much of it is trial and error.

And actually, a lot of the breakthroughs that I’ve had in my art practice have come through errors. What you might see as errors, but they’ve actually been something that I want to keep because I think, “Oh, actually, that’s a breakthrough. It’s really worked.

It’s really good, but it was unintentional.” So I think it came from just years of doing things, and I realized that’s what I liked the best. So from that really.

Zoë: Can you tell us a bit about your artistic journey? Were you always interested in painting and were there any particular styles or mediums that you experimented with?

Fiona: Yes, I’ve been interested in drawings and paintings my whole life. I experimented with different styles and mediums, but a lot of it depended on practicalities.

For example, when I became a mom, I couldn’t use oil paints anymore because of the toxicity of the thinners and other chemicals. So, I switched to acrylics, which are much less toxic.

And when I didn’t have a studio, I went back to my drawings or worked on smaller pieces. As a woman artist, you have to be flexible and adapt to your circumstances.

Zoë: Speaking of women, can you talk about the subject matter of your work? I’m looking at the piece behind me, which reminds me of the title “Start Here”. Can you describe any of your works and the themes behind them?

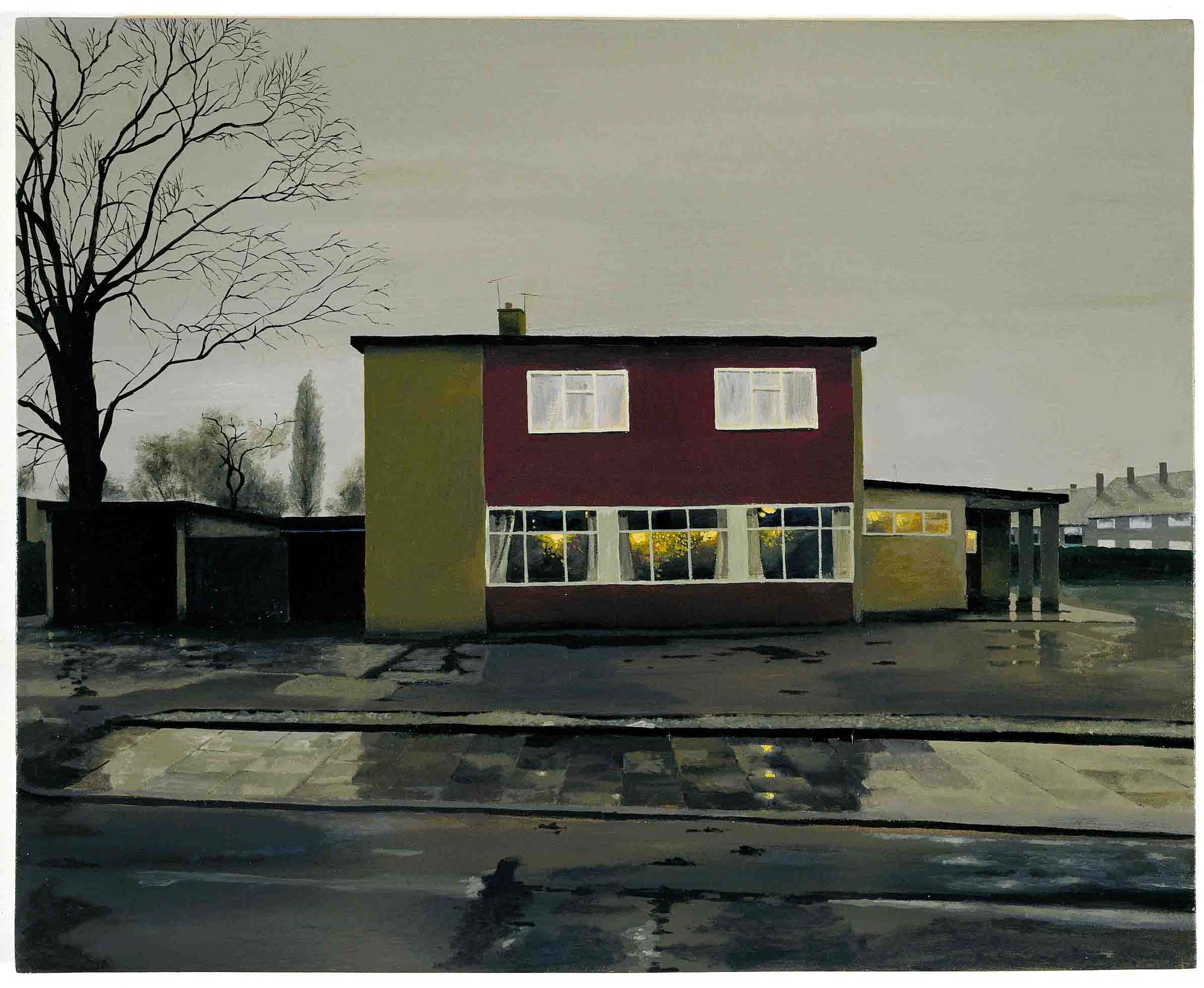

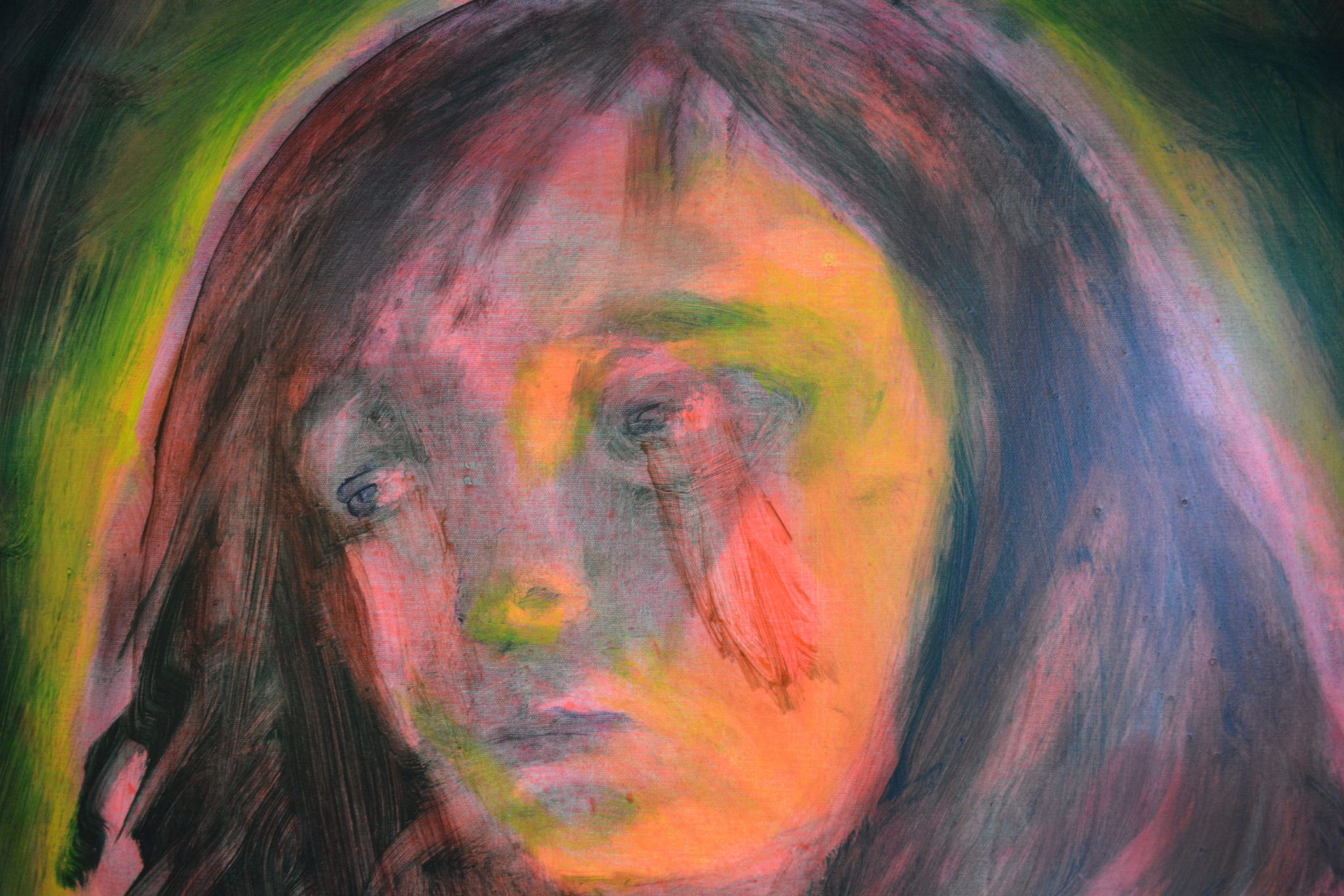

Fiona: Well, as you can see, some of them aren’t gender-specific. That’s true, but a lot of them are women. And I’m fascinated by the human condition, by how the world is navigated and negotiated through emotions, and by what it’s like to be a woman in the world.

I often work in series, and in this latest one, most of the subjects have red hair. This is because my mother and brother-in-law both died recently, and they both had red hair.

Since their deaths, I’ve been compulsively making paintings of people with red hair, without even realizing it until my husband pointed it out to me. I think a lot of artists work subconsciously like that, with a compulsion to create.

It’s only afterward that you realize what you were doing. I think sometimes I’m conveying emotions or working through them, sharing them.

The latest series is about that, but they’re not specific portraits of my mother or brother-in-law. They could be seen as portraits of emotions or, as the arts writer Paul Carey-Kent wrote about my recent show, “non-portraits of real people.”

They’re about loss, grief, remembering, and emotions. Does that make sense?

Zoë: When you look at figurative painting, it’s not so much a trend, but it’s what I’ve found with artists. They really understand that it’s an extension of the self.

It’s a perfect expression, drawing somebody else, but even if you’re drawing someone else, it has your own sense of identity because it’s your interpretation of that person.

But it’s also in your memory, so it does make sense. It’s not coined your own phrase, but it’s an observation of humanity.

Fiona: That’s right. And the other thing is, well, that’s just made me think about Oscar Wilde, who said that every portrait painted with feeling is really a portrait of the artist.

And also, although they’re about individual feelings and emotions, because those emotions are universal, we all go through them, like grief.

So there’s a kind of universality to it that I hope people will recognize and relate to. It’s not just about me and from me, but it’s something that’s universal that others can relate to as well.

Zoë: For the bonus questions that we do for Cosimo, it’s all about making art accessible, reaching out to emerging artists, and we like to have artists’ insights for any artists listening, or for patrons or collectors as well.

What do you love most about being an artist? If you can pick one, it can be several, but if you can pick one.

Fiona: Just making the art, just making the work. I love it. I’m compelled to do it. And when it goes well, it’s the best feeling in the world.

But when it goes badly, which happens a lot, it’s the opposite. So just making the work, solving those problems and seeing what emerges on the canvas.

Zoë: Has art always been a form of therapy for you, or is it just more recent with this recent work?

We’ve done a lot of things about memory and nostalgia, and it’s interesting. It really is like this sense of a symbiotic relationship that one artist wants to impart between artist and viewer, that they have their own subjective ideas about what the story of the painting is and what trauma or nostalgia it invokes.

Fiona: As an artist, I don’t think I ever for a minute thought of it like that. It was just something I liked doing. There’s something so meditative about it, and it takes you into a different space of thinking.

And when you’re making the work, you can’t think of all those other things. So, in a way, there’s something a bit Zen, a bit meditative about it.

But I never thought, “This is therapy.” I just feel compelled to make it. If there’s some sort of therapy there, then that’s great, but it was never my intention.

However, we know that art therapy exists for a reason, so maybe it comes together somehow.

Zoë: Yeah. And with artistic influences. This goes back to still art making, or we can go with what you love about them.

Do you draw from any? It’s okay, don’t worry about it. Yeah. I’m trying to draw from any artistic influences, or do you have any? Did you have any inspiration?

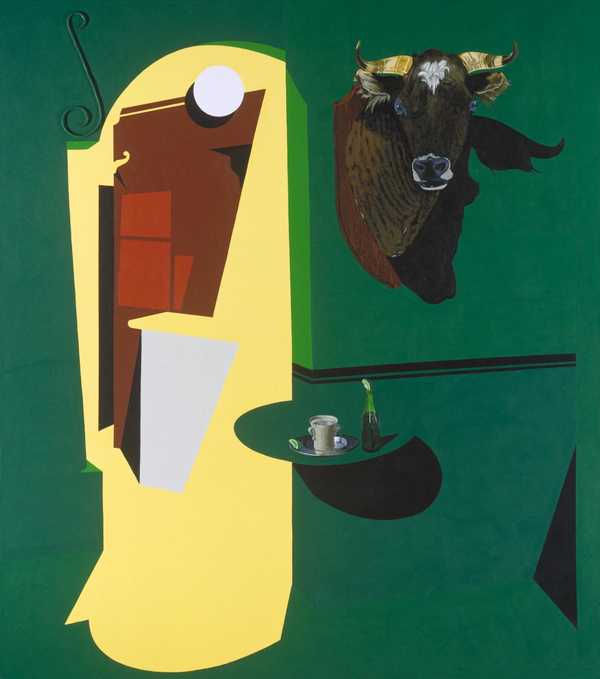

Fiona: Yeah, I mean, obviously, as an artist, I’m fascinated by our history. I mean, my daughter when she was little, she said, ‘Please, mommy, no more art galleries.’

We were constantly looking at art. I suppose, off the top of my head, Marlene Dumas. Love her work, especially her inks, but also her oils as well. I mean, she’s an amazing female artist.

Alice Neel. Fantastic. I mean, just beautiful. And again, a female artists – both doing similar subjects to me… Chantal Joffe, I mean, I adore her work. She’s just amazing.

Zoë: Why did you focus on women as subjects, or do you have any other things that really make you compelled to be, and not just because you’re a woman?

Fiona: Again, it’s because it’s so instinctive, it’s really difficult to answer that. But I think that’s a good thing. We maybe already answered it in that I just feel compelled to do that as what I want to do.

I don’t really, you know, to keep kind of in touch with like to be authentic, I almost don’t want to analyze it too much. I just want to do it. You’ve got to kind of be in touch with yourself and just do what you want to. I found a book that I made when I was 12, and it was kind of similar things.

I was doing it then. I mean, I have done other, I’ve done landscapes, and I’ve done, you know, I’ve done all sorts of things over the years. But I come back to this. It’s just, it’s what I want to do mostly. And that’s it. It’s sort of as simple as that, I think.

I really believe that. You’ve got to be authentic. The best art, I think, is the most relatable art when you are authentic and you’re just in touch with what you want to do, and you’re doing it because you want to do it.

Yeah. And that’s it. You shut everything else out because nothing else matters. So this is where I want to be doing this if I was with a gallery or not with a gallery, if I was paid or not paid.

I would be doing this.” I honestly think it’s pointless unless you’re going to be authentic. That’s what I feel, that’s true. It’s taken me a while to acknowledge that and realize that, but I think it’s absolutely vital.

Zoë: Did you find, as you’ve gone through your career as an artist, that the best thing to do is to make work that you love?

Did you ever fall into trends that you said, “I have to sell?” Or do I have to be pressured by people to do that? Certainly, that’s part of the journey.

Fiona: It’s very easy to say, but it’s not always easy to stay authentic. Yeah, it’s all part of the journey, and at various times, you have to be flexible and do things that maybe you wouldn’t want to do, really, but you might be part of a course you’re doing, might be part of what a gallery wants you to do, or you might be influenced by what other people are doing.

And all those things are fairly valid parts of your artistic journey. You have to do them sometimes. But at the end of the day, the best work comes when it’s just from the heart.

Zoë: And so however you would like, what would maybe be your least favorite thing about, let’s say, the art world? If you can, you can take care of a few.

Fiona: I think we touched on it already. And I think it’s the sexism, you know, the inequality. When I was doing my Masters, part of that was to do a project and give a presentation about sexism in the art world.

As someone who is quite switched on about things like that, because I went to LSE and I’ve done research, I was even shocked at how bad it is. You know, there have been some inroads, but there are some terrible statistics about how bad it is in the art world.

Even now, I’m not talking about 50 years ago. In art schools, women make up 60 or 70% of art students, way outnumbering men. So they’re quite happy to take our money for that. But when we’re out in the world, our participation is hugely reduced.

We’re only in far fewer shows and have far less representation in galleries. I was looking at some figures the other day. The National Gallery, which has 2,000 works, has only 21 by women.

Yeah. In all the top galleries, those with the big owners, we make up only 7% of art in top galleries. And there are just some horrific figures, really.

For example, when we have artists represented by commercial galleries, in Europe and North America, only 13.7% of living artists are women. This isn’t the past; this was from last year.

Zoë: I think it’s still 2% that make up the top tier art market. Yeah, I don’t think that statistic…

Fiona: Yes, 2%… We know sexism is everywhere but I would honestly say it’s worse in the arts than in all the other things that I’ve done.

And I tried to work that out. I tried to kind of think, why would that be? And I think it’s because in the arts, we’re not used to quantifying things and counting things.

Yeah, if you worked in a bank, you could say, there are X number of women in this bank and X number on the board, and we need to change that. It’s not fair. You can count them. It’s very specific. It’s very easy to do. And in fact, it’s done in the banking world.

They probably haven’t achieved parity, but they try to. In the arts, they can get away with saying, “Well, it’s a meritocracy. It’s, you know, they’re just not good enough. It’s all subjective.” It’s like, “I don’t like their work”. There’s no objective measure.

And that system is open to abuse. And indeed, it is abused. Otherwise, why are we making up 60 or 70% of the art schools and then getting just crumbs when we come out?

The system is very difficult to police because it’s so open. Of course, you can argue that it needs to be open; it’s about creativity.

Yes, of course, we need to be open, but I think we could take it seriously. We could put measures in place to make it better for women.

It’s not just about sexism, but there’s racism, and we should be trying to achieve parity, thinking about it and working towards it. I’m not saying it’s easy, and I’m not saying we’re going to do it overnight.

Zoë: Is there any advice that you can impart on any aspiring or emerging artists who are making this decision to choose this career path?

Fiona: On a practical level, I’d probably say you’re probably going to need a day job unless you have family money. Seriously, you need to have a roof over your head and food to eat.

So, having a day job is a good idea. Then the advice I think, be true to yourself. It takes time. You’re in it for the long haul. It’s not a sprint. It’s a marathon, and you’re going to change along the way.

Try to be true to yourself. Don’t be too hard on yourself, try to have self-confidence in your work, at least, if nothing else, just believe in your work.

It’s your work, it’s come from your heart. So, have confidence in what you’re making. Don’t think too much about whether your work will get into a particular gallery or show.

If you do that, you’ll lose your authenticity, and that’s really important to make meaningful work for yourself and others. Just believe in yourself and don’t give up.

Zoë: Okay, great. That’s encouraging to know. Is that all for this project?

Fiona: Yes, just for the next few months. More to come. Thank you so much, Zoë, for having this discussion. It’s been great.

Zoë: Super, thank you so much. I really enjoyed it.