By Zoë Goetzmann

Interview with Mia Hawk – Pop Art Illustrative Artist

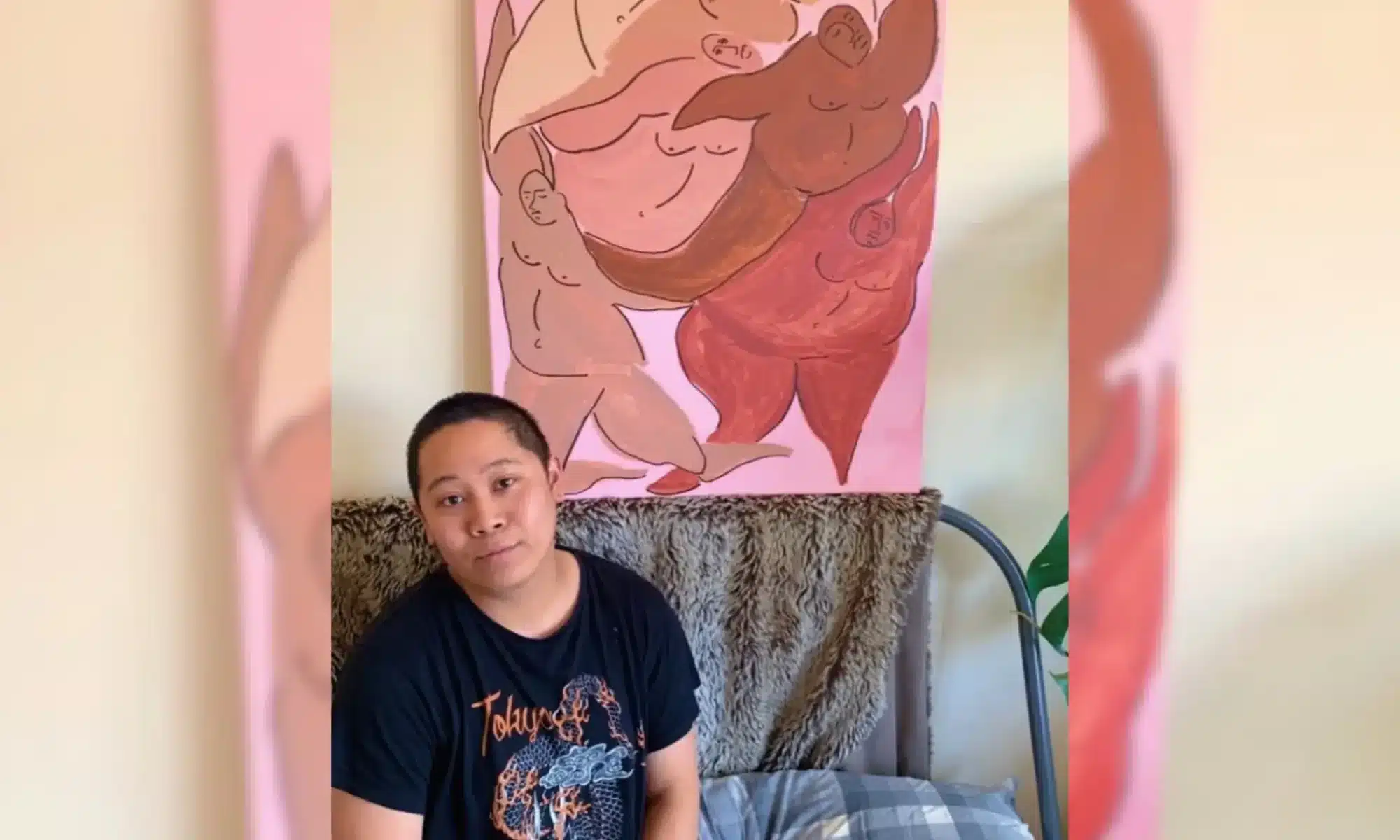

This week on Cosimo Studio Tours, we stopped by artist Mia Hawk’s (@miaskyhawk) studio in South London.

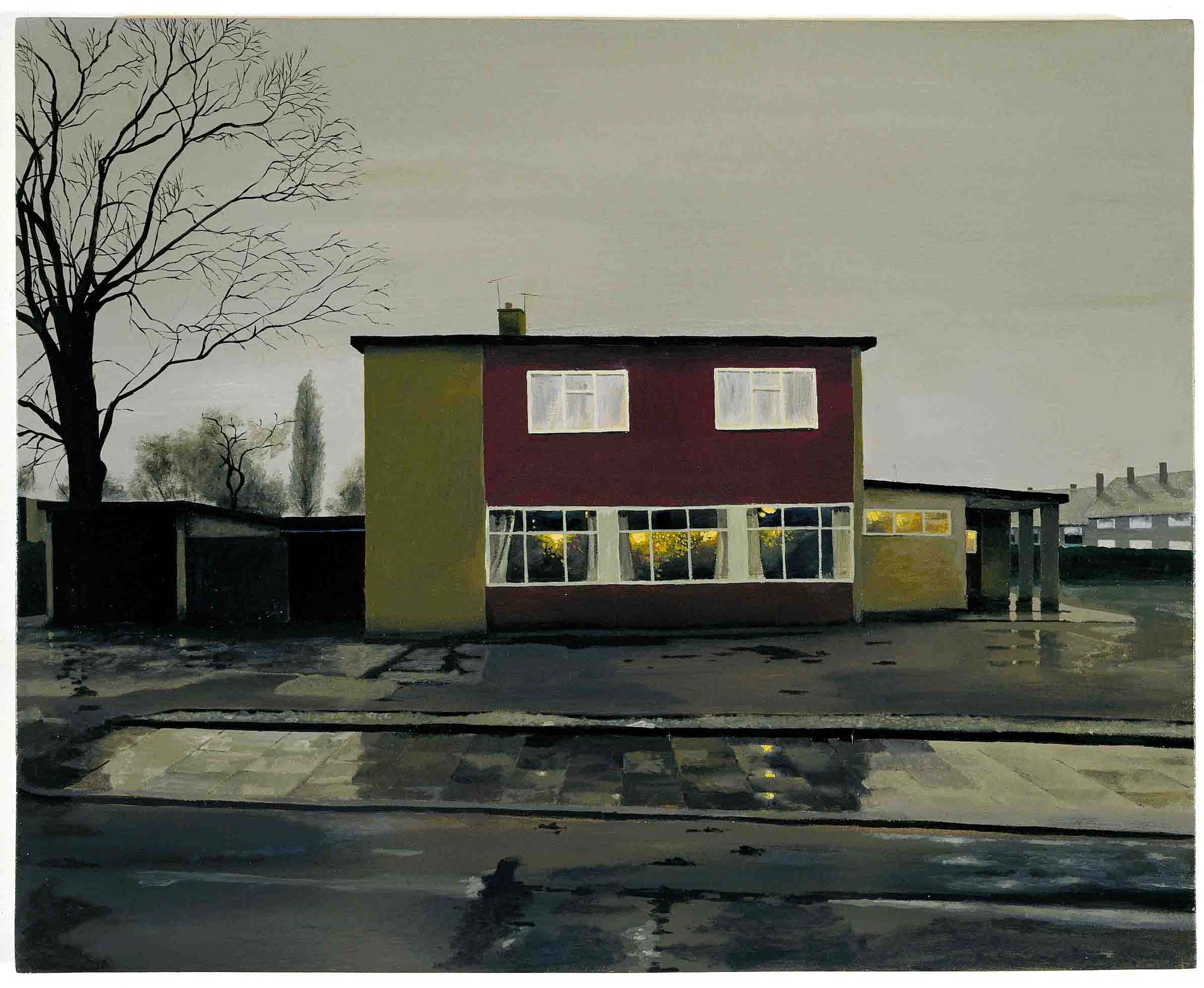

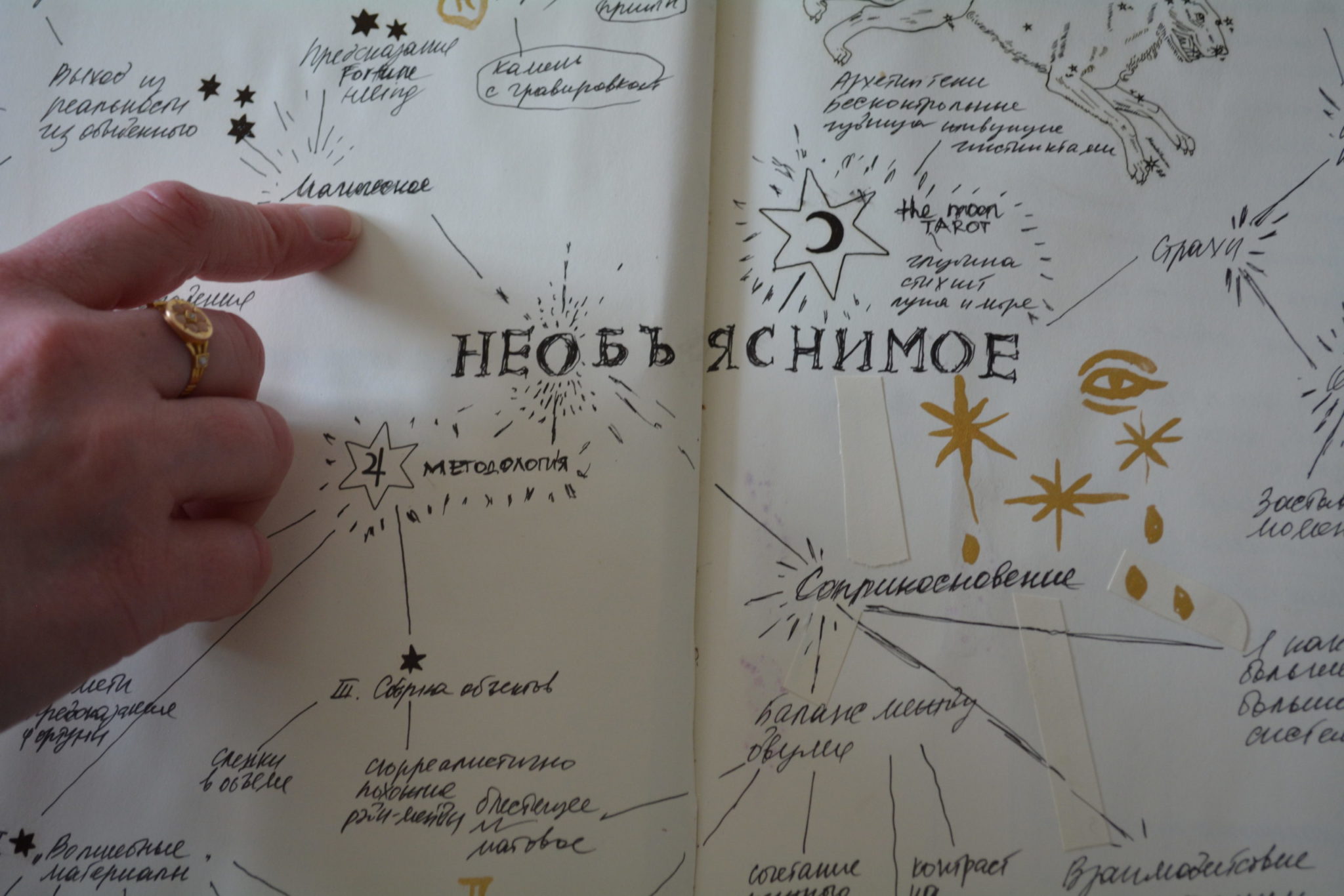

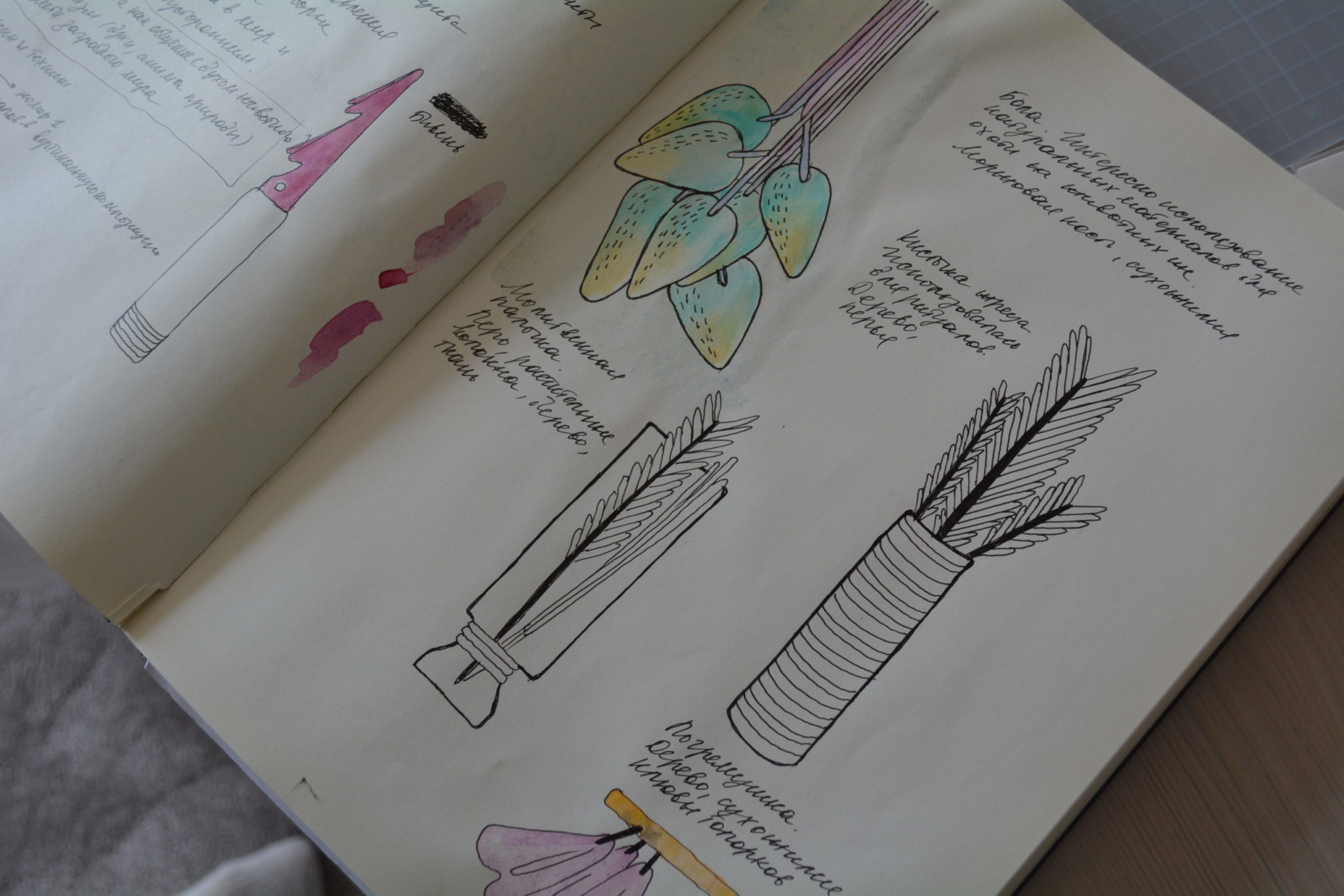

Mia is a full-time artist who works in a variety of mediums and artistic disciplines, from hyper-realist paintings to surrealist, pop-art illustrative works and designs.

In this interview, we delve into many different topics, including social media, the art world of Instagram, the female vs. male gaze, how Mia balances both the entrepreneurial and creative sides of her artistic business and career, mental health, as well as, her multi-disciplinary approach to creating her bold, expressive, imaginative (often funny and/or humorous) works whether they be fine art, digital prints, or silk-screened creations.

You can find (and see) Mia, her artwork, and her designs in person at Canopy Market in London, where she will be showing her artworks in an exhibition in October 2023. She will also exhibit her works at Ruby’s Rooms in Hastings next month.

Zoë: Thank you so much, Mia, for being here with us today.

Mia: Thank you, it’s really exciting!

Zoë: So, the first question we’ll delve into is your artist story. Can you tell us how you became an artist, the journey that you took to get to this profession or just your art career?

Mia: I think I always knew I wanted to be some sort of creative when I was growing up. That was never a question.

However, I never thought I would end up as an artist or a painter. When I was a kid, I used to draw just for fun. My best friend and I used to draw Pokemons and watch Disney films when it rained, which was quite often since it rains a lot where I’m from.

My first choice was actually to become an actor because I had watched so many films growing up, and I was completely lost in the amazing worlds that people had created.

So, I pursued the Norwegian equivalent to acting A-levels and then got into a UK drama school that focused on actor-musicianship. I went there for three years, graduated, and then worked as an actor.

However, while I was in between acting jobs, I was doing a soul-destroying market research job where I had to take down verbatim what the client was saying. I started doodling in my notepad in between because it was so boring.

I realised it was kind of fun, and I used to draw, so I started making these little characters that would look really cool on a t-shirt. I taught myself how to screen print t-shirts, and that became a bit of a hobby.

I started doing more illustrations and thought to myself, “why don’t I sell this to the market? Maybe I can do a side hustle doing this.” So that’s kind of how it started, and then I started selling at markets for about five to six years.

Around 2014, I was doing some quite long, big acting jobs, and I realized that I was putting every penny I earned into this art business. By that point, I had probably been drawing again for four or five years, and I had started painting more figurative art.

My painting journey was really evolving, and it wasn’t just small, fun animal drawings anymore. It was big figurative pieces, and I started moving into my hyperrealism.

I was like, “Wow, it’s kind of a lot having two careers. Why don’t I just go into the art thing and see how that is? I can always pick up acting if I don’t want to do it anymore.”

So, I went full-time artist, mainly going through an independent route.

All the commission work and all the stuff that I do mainly comes through social media, people that have met me at markets. It’s kind of just evolved since then.

During the pandemic, I delved into animal art, and I got loads of commission work doing bird art pieces, and that became a thing. Then I started Patreon for that. Last year, I had a big shift, moving away from the hyperreal animal stuff into more of what I’m doing now.

Now, my business is doing craft fairs, having a couple of big commission works on the go, selling through social media, and doing art fairs every so often.

But, my journey has been independent… And I’d also add I’m an introvert, but I’ve got a very extroverted energy, so when I’m passionate about something, it just explodes outwards.

Zoë: So, you are a full-time artist. Before we go into your art practice, did you go to art school?

Mia: No, I didn’t go to art school.

Zoë: That’s interesting. So, how did you practice? What was your routine when you first started drawing or painting? Aside from when you were a child, how did that work? Or when you decided to make this jump into art, how did you set up your learning practice?

Mia: I think it was very much interest-driven. So, at first, it was about getting together stuff for a business. And then, it was very much interest-driven. Like, “Oh, I really want to create something specific.”

When I was learning how to do portraits, for example, it was very much like, “Oh, I have this idea for a portrait. I don’t know how to paint hair. I need to learn how to paint hair.”

Then, I had to buy lots of books. In terms of having a practice, I grew up playing music, and I learned how to be disciplined. It gave me a really good understanding of how to get good at something. It’s basically practice and learning, having a good basis of understanding.

Actually, I would say one of my biggest weaknesses is that I’m not that great at drawing. I’m not as good as I want to be. It takes me a long time to do a good drawing, but I’m very good at painting. It’s very funny.

Like, painting, I really get along with it. Drawing can be difficult for me, and it takes me a long time to get my head around it.

But because I played in brass bands growing up, and they were very good, there was an understanding that if you want to get good, you’ve got to practice every day, and you’ve got to do your scales, you’ve got to do your warm-up.

So you’ve got to do everything. You can’t just wish that you’re good at something; you’ve got to put in the work. I think I applied quite a lot of the same mentalities that I learned from playing an instrument.

Yes, it does take a long time. For me, it takes about five years to consistently practice something to get intermediate to very good at it.

You’ve got to put in the 10,000 hours or whatever it is, but that also gave me the understanding of if I really want to learn this, then I’ll be able to do it.

It’s not a matter of necessarily having a specific talent. I would say my talent lies more in having vision, being a good visionary person, and composing and storytelling.

Zoë: Can you say what you love most about being an artist, if you could pick one thing?

Mia: It’s definitely like you feel like there’s an overload of inspiration. So, it’s just the feeling of possibility, like, “Oh my God, wouldn’t it be cool if we’re like, ‘Oh, that would be really fun!'” Or, seeing things that you have as an idea in your head coming to real life can be quite an amazing experience.

The creative process can be very frustrating, but it can also be incredibly pleasurable. When you have one of those paintings where everything just flows, it’s a really amazing experience.

So, I think that’s a very positive thing about the practice. The second thing I would say – you said one, but I’ll give you two – is when you find someone who loves your paintings, or when you’re doing commissioned work, and they just love it because you connect with people on what they love. If they really connect with your painting or what you

Zoë: I think that’s great, though. I mean, that’s what Cosimo is, it’s a little bit more independent. We’re making our own bridges. That’s why.

Mia: That’s fantastic. I love that. I guess I’ve never really felt like I connect with the art world in the same way that maybe other people do.

Because I didn’t go the art school route, it feels a bit foreign to me. It can feel unapproachable at times. I try to network by going to openings at least once or twice a month, but that’s not a lot. It takes a lot of time running your own business – so, it can be difficult.

For me, the art world can feel a bit unapproachable at times. I find it difficult because, like it does take a lot of time running your own business.

So, you know, things like things that I need to be better at, for example, like networking, like I try and go to like openings and stuff and I try to go out and see at least like once or twice a month.

That’s not a lot… But you know, it’s it’s kind of like what I can manage on top of my already like huge workload and I also need to actually have a life!

And I think I think I maybe lack a bit of knowledge, because I’m perhaps like a lot of artists…we’re good at the creating, and it’s perhaps more difficult to relate to some of the galleries.

I find it difficult but haven’t really put that much effort into it either, to find where I fit into it, because if I can do things myself, I will try and go that way. I just want to show my work to people. And it was really that simple.

Zoë: I think that’s great. That’s the freedom of doing it yourself, which is the benefit of being independent… Do you have any advice for other people who are starting out as artists or who might be thinking about it as an option?

Mia: Like, don’t do it unless you can do it. Like, it’s not an easy journey. It’s not an easy life, and you sacrifice a lot of things. So, don’t do it unless you can’t not do it. Unless that drive is there.

Zoë: Okay. Do you have any advice for emerging artists going into this career path with the hope of becoming a full-time artist?

Mia: My advice is to read up on business, and understand that running your own business takes a lot of work. Sacrifices have to be made, but if you have the drive and the passion for it, it’s worth it.

Zoë: I think that’s good. Yeah. No, I thought it was more like don’t do it. I thought you were talking about like a part-time job, like a half-time job. I thought it was like an economic also an economic thing. Probably, whoa, I like Okay, so this, I always have this need to create, create because you love it. Yeah. And…

Mia: Then. So it’s that, I mean, the thing is, there isn’t a straight-up answer because everyone has, like, probably the best advice is to understand that you are going to have to find your own way through this.

And, and it’s going to be a combination of things. So obviously, what your style is, where does that fit in? Where’s your audience?

Like what business model works best for you? Like some people don’t like selling in person. I find it exhausting. But I also like it, for example, I like being on social media, I like talking to people, sharing, you know, so that really works really well for me.

Some people it might be art licensing, and that works really well for their style and their business. And they’re gonna get, you know, some people it might be selling stickers online, or whatever, you know, because they know how to hack that.

And they’ve got that. And so it is really and some people it’s going to be getting into a gallery, some people it’s going to be doing a lot of commissions because that’s what they love to do. So it is really like kind of exploring things, seeing what you are comfortable with.

And kind of for me that like a lot of this with the new style was me also realizing that, you know, I’ve got to work with my own energy, which isn’t actually to sit still and do a lot of detail work.

And I need to actually create art that more reflects how I work as a person. Also, like, yeah, consistency, probably be consistent in the things that you do.

When you try things, try it a few times, not just once, because you never know, especially with markets, you might have a good day, you might have a bad day, you never know until you’ve done a few how it’s going to be.

I would say don’t be afraid to try something else if one thing isn’t working. Like, don’t get so stuck up on one idea that that’s how it’s going to go through that you know that it that you’re afraid to give up almost like I’ve changed styles, I’ve changed tactics so many times.

Sometimes maybe that was a bad idea. Sometimes it was definitely a good idea… Just have integrity I would say.

Zoë: That’s helpful. Is there anything specific that you would like to highlight or focus on?

Mia: Yeah, I mean, I now, as many people do after the pandemic, suspect that I might be neurodivergent. I don’t know because obviously, I don’t have a diagnosis and it’s a very long waiting list to see.

But I’ve always had certain issues with my mental health that have been very perplexing to me that are now falling into place.

And now that I understand myself better, I’m creating ways of doing things that are making my life so much easier. For example, changing my art style into something that goes with my energy more, so that I don’t have to sit still for five hours to do one painting, for example, has been massive for me.

That’s been really, really positive. I know, for example, that I need to keep exploring and always pushing things forward. So that’s one reason why I created this style, to accommodate my need to keep exploring.

So, my advice would be – and this is what I’m working on at the moment and which I think, if I understood this a bit further a lot before, probably would have made my life a lot easier – try not to focus your practice on outcomes.

I don’t wait like, “Oh, my life is going to be solved when I get that big exhibition” or “when that big exhibition happens, that’s all I’m working towards” or “that acclaim” or “that whatever it is”.

It’s like put your effort into keeping the system going, if that makes sense?

Whether that means, okay, have I had my daily or weekly website checkup? How’s my social media doing?

And also scheduling in things like, “Remember to have fun. Have you painted anything fun recently?”

It’s very much like creating a system that supports you is what I’m working on. And instead of working towards a big show, it’s like I’m creating habits where the byproduct will be a big show, or where the byproduct will be having enough paintings for an art fair or where the byproduct will be networking enough to…

Like that’s where I’m putting my focus, rather than achieving things, if that makes sense.

Zoë: That’s such great advice, well thank you, Mia. This has been a really good in-depth conversation.

Mia: You’re so welcome. Thank you!